Wystem Architecture Part 2: Technologies of Connection

We have argued many times that challenges like climate change and social inequality defy simple solutions, we need new ways of bridging divides - between disciplines, between local and global knowledge, between theory and practice. The philosopher as connector (one of four types we mentioned last week) emerges as a crucial figure in this landscape, serving as a "philosophical ecologist" who maps relationships between seemingly disparate domains of knowledge and action.

This connecting role takes on special urgency when we consider how technology and design shape our world. As we've seen with social media platforms, technology can either fragment or unite, either erode or build trust. The challenge is to create what we might call "wisdom-centric connections" - technological and social infrastructures that don't just enable communication but actively promote understanding, empathy and collective intelligence.

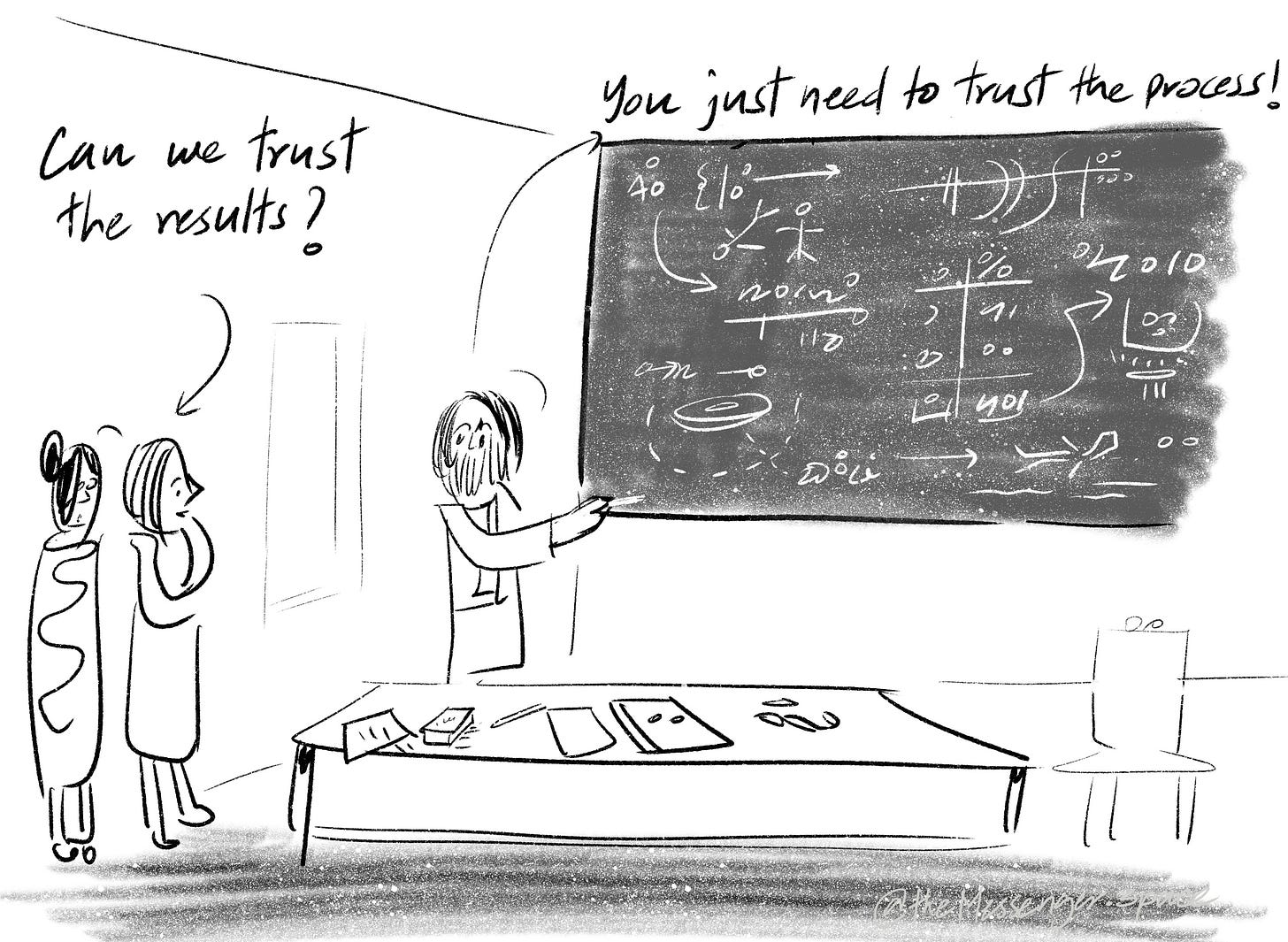

The philosopher-connector must therefore work closely with designers and technologists, helping ensure that new systems serve genuine human and ecological needs. This means going beyond both traditional philosophical reflection and conventional design thinking to create what the Wystem approach calls "trust architecture" - frameworks that make connection meaningful rather than merely efficient.

By bringing together philosophical insight, design methodology and technological capability, the philosopher-as-connector can build technologies of connection that foster wisdom rather than mere interaction. These technologies are essential tools for bridging divides and creating meaningful relationships in an increasingly complex world.

Technologies of Trust

Once upon a time, there was a friend, a real charmer, a man with the warmest welcome and the heartiest praise. Turns out he was more of a flatterer than a friend. The minute you turned your back to him, he would bitch about you to anyone within earshot. Not a man to be trusted!

Trust is the glue of human existence. We wouldn't be able to cooperate if we didn't trust each other. Actually, we wouldn't even be able to compete if we didn't trust each other. When I face you on the cricket field, I know you're going to play your best to try and defeat me, but I also expect you to obey the rules of the game. If I didn’t trust you would or I suspected you wouldn’t, I would behave rather differently.

Unsurprisingly, technologies of trust are among the most important technologies ever. Humans who live in small communities, perhaps like the ones that we evolved in, establish trust through repeated personal interaction. But those of us who now live and work with strangers, sometimes on the other side of the world, need something else to establish trust.

We need technologies of trust.

Money is arguably the most important. I can go to a store, present a piece of paper, and walk away with a loaf of bread in my hands. Magical, isn't it? Money is an incredible technology of trust, one backed by the state. But money commodifies trust, turning it into a transaction, which is fine for some circumstances but not for others. We can all imagine situations where we don't want to turn trust into a transaction, but rather into connection, which means that we also need technologies of connection.

What might they be?

Cautionary Note

Let's sound a note of caution before addressing that all important question. Social networking is certainly a technology of connection. People have used these services starting with MySpace, then of course the immense expansion of Facebook, Instagram and TikTok along with chat technologies, WhatsApp most prominently, to connect with others.

People from across the world have formed connections on these apps, both people who have known each other in the real world as well as complete strangers. These good things realize the promise of social networking but we would be blind if we didn't recognize that those very same technologies have been twisted for malicious purposes.

There is no doubt that now social networking is a technology of trust that has been weaponized and has become, in fact, an instrument of repression, anger, sometimes even genocide. So when we talk about technologies of trust, especially technologies of connection, we have to recognize that there's no such thing as a pure technology, one whose purpose cannot be corrupted.

Technologies of Connection

That's why we need to think carefully about how to design technologies of connection that resist corruption and misuse. The answer might lie in understanding what makes traditional forms of connection resilient. Face-to-face communities, for example, have built-in mechanisms for accountability. When you know someone personally, when you see them regularly, when your reputation in the community depends on your behavior, you're less likely to abuse trust.

The challenge then becomes: how do we build these accountability mechanisms into digital technologies of connection? One approach might be to prioritize local networks over global ones. Instead of trying to connect everyone to everyone else, we might focus on strengthening existing community bonds and facilitating connections between neighboring communities. This "network of networks" approach could help preserve the benefits of technological connection while maintaining the natural constraints that traditionally helped keep human relationships healthy.

Another crucial consideration is the role of reciprocity. Traditional forms of connection often involve mutual obligation and shared responsibility. Modern technologies of connection, by contrast, often emphasize frictionless, commitment-free interaction. While this might seem convenient, it may actually undermine the very trust these technologies are meant to build. Perhaps what we need are technologies that don't just enable connection, but actively encourage investment in relationships and community building.

From Technologies of Connection to Common Source Organizations

Having explored the need for wisdom-centric technologies of connection that resist corruption and build meaningful relationships, we must now ask: what organizational structures can embody these principles? The standard model for civil society organizations--borrowed from the traditional firm--may be fundamentally misaligned with the trust architecture we seek to create.

The traditional firm exists to solve a specific problem. As economist Ronald Coase explained, firms reduce the costs of constantly negotiating with strangers in the marketplace. Instead of haggling over every transaction, firms create internal hierarchies where an entrepreneur directs resources and production. This works well when the costs of managing internally are lower than the costs of dealing with the market.

Computing has changed this equation dramatically. Platforms like Uber make it easier for individual drivers to find customers without needing the structure of a taxi company. Yet some relationship-based businesses remain strong. Your local corner store survives because it provides something beyond mere efficiency--it offers trust, personal relationships, and intimate knowledge of what the community needs. Traditional organizational structures force a false choice between local, relational knowledge and global, scalable systems. What if we could integrate both instead?

Wystems Thinking 7: Common Source

This week's Messenger is inspired by a friend and leader who called out Socratus as an extension of the organization he leads. Which prompted us to ask:

A couple of months ago, we proposed "Common Source" as a way of architecting organizations. Unlike traditional firms that treat knowledge as proprietary and staff as assets, common source treats knowledge as a public good and people as collaborative agents who can move between contexts while carrying their expertise with them. If traditional firms are like organs in a body, each with a specific, contained function, common source is like the blood or breath that flows throughout the system, transporting nutrients wherever they're needed most.

Common source creates natural accountability mechanisms through transparency and shared ownership, similar to face-to-face communities but scaled digitally. Second, it embodies genuine reciprocity through shared knowledge and expertise, encouraging investment in relationships rather than frictionless, commitment-free interaction. Third, it enables simultaneous local responsiveness and global knowledge sharing, avoiding the false choice between community bonds and broader connection.

Rather than trying to connect everyone to everyone else, common source creates networks of networks. It strengthens existing community bonds while facilitating connections between neighboring communities through shared expertise and transparent protocols. For civil society organizations facing complex challenges like climate change and inequality, common source offers a practical way to implement wisdom-centric design. By making both intellectual property and human expertise freely available across ecosystems, it creates conditions for collective wisdom.

In short: common source embodies the technologies of connection we desperately need: systems that don't just enable communication but actively promote understanding, empathy, and collective action.

Conclusion

Technologies of connection are critical infrastructure for collective wisdom and action. However, as social media platforms demonstrate, technology alone cannot guarantee meaningful connection - it can either unite or fragment, build trust or erode it. The key lies in designing what we've termed "wisdom-centric connections" - technological and social architectures that actively promote understanding, empathy and collective wisdom.

The philosopher-as-connector plays a vital role in this landscape, working with designers and technologists to ensure new systems serve genuine human and ecological needs. By bringing together philosophical insight with design methodology, we can create "trust architectures" that make connection meaningful rather than merely efficient. This involves understanding what makes traditional forms of connection resilient - like face-to-face community accountability and reciprocal obligation - and translating those principles into digital technologies.

Common Source organizations offer a promising model, treating both knowledge and expertise as public goods that can flow freely across contexts while maintaining accountability through transparency. By making intellectual property and human capabilities openly available, Common Source creates natural conditions for collective wisdom - enabling simultaneous local responsiveness and global knowledge sharing. This represents the kind of technology of connection: systems that don't just enable communication but actively cultivate understanding, empathy, and collaborative action in service of addressing our most pressing challenges.