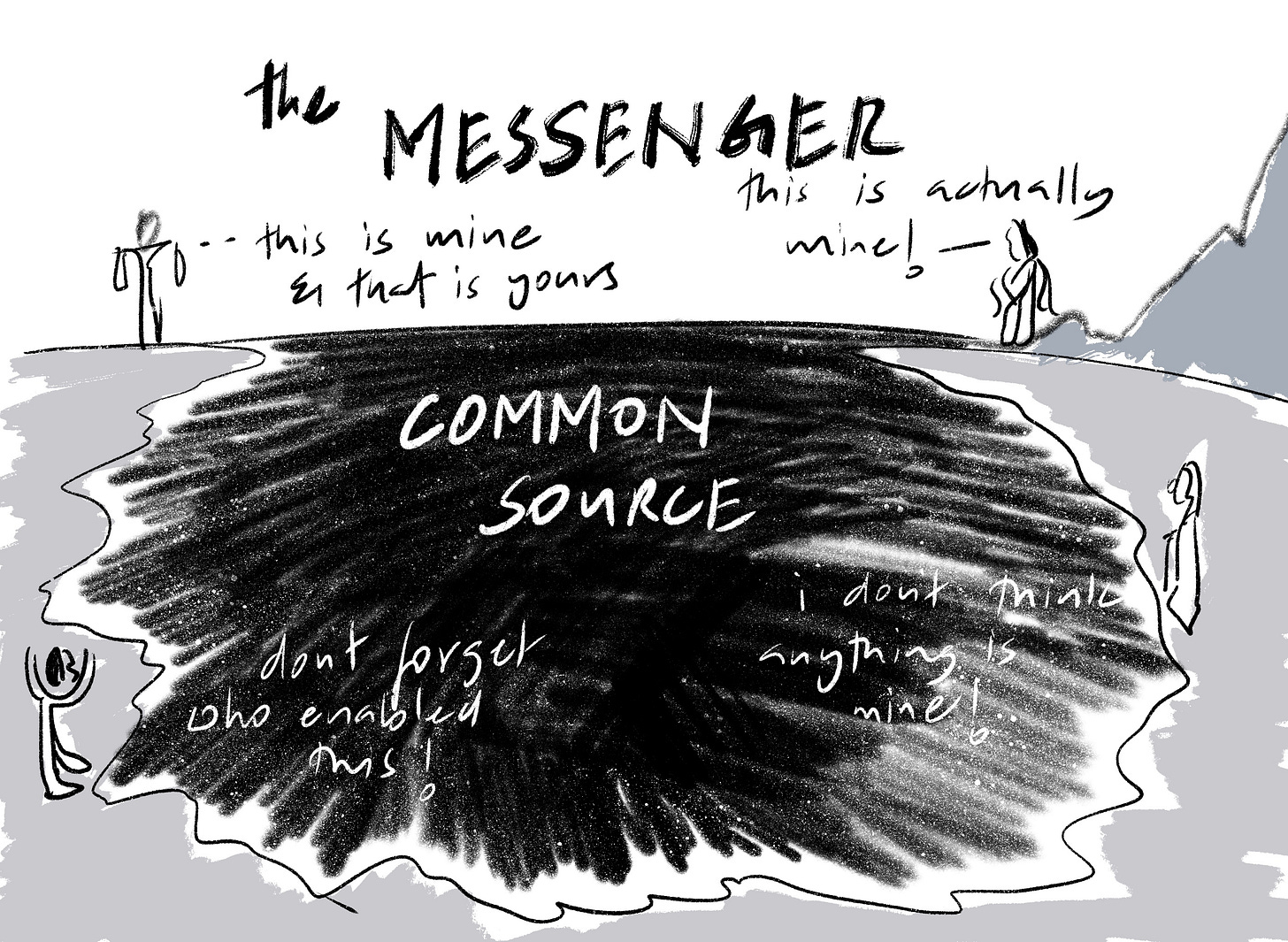

Wystems Thinking 7: Common Source

This week's Messenger is inspired by a friend and leader who called out Socratus as an extension of the organization he leads. Which prompted us to ask:

How should civil society organizations be designed?

The standard model of a civil society organization is that of a firm - an enclosed environment whose staff work full time for the organization (which inherits their IP etc) and whose interface with the world doesn't reveal any of its inner functions.

Is the firm the right model for mission driven organizations?

Beyond the Traditional Firm

Ronald Coase's theory of the firm, presented in his 1937 essay "The Nature of the Firm," explains why firms exist and what determines their size. Coase argued that firms emerge to reduce transaction costs associated with market exchanges, such as finding prices, negotiating contracts, and enforcing agreements. These costs can be significant, particularly in situations of uncertainty or asymmetric information.

Within a firm, market transactions are replaced by hierarchical organization, where an entrepreneur directs resources and production. This is more efficient for certain activities because it minimizes the need for repeated contracts and negotiations. However, firms face internal costs, such as diminishing returns to management, which arise as they grow larger and more complex. Coase concluded that a firm will expand until the cost of organizing an additional transaction internally equals the cost of conducting that transaction in the market. The balance between transaction costs and internal organizational costs determines the optimal size of a firm.

Computing reduces market costs, which you can see in the rise of platforms. Uber and Ola make it easier for an individual driver to find customers - the driver doesn't need to park himself at an auto or taxi stand anymore (the stand being the equivalent of the firm). Equally importantly, the driver doesn't need to have a personal relationship with the people of a particular locality who use his services over other drivers. On the flip side, some types of small firms are sticky, especially when they leverage human relations - such firms are hard to replace with aggregated platforms. Kirana stores are a good example: they perform an essential local function by taking away the challenges of item discovery and credit (including carrying change). Aggregation and platformization changes the dynamics of supermarkets and kirana stores. If anything the local store's niche is more robust while Swiggy or Zomato can perform all the functions of a supermarket without any of the hassle of shopping.

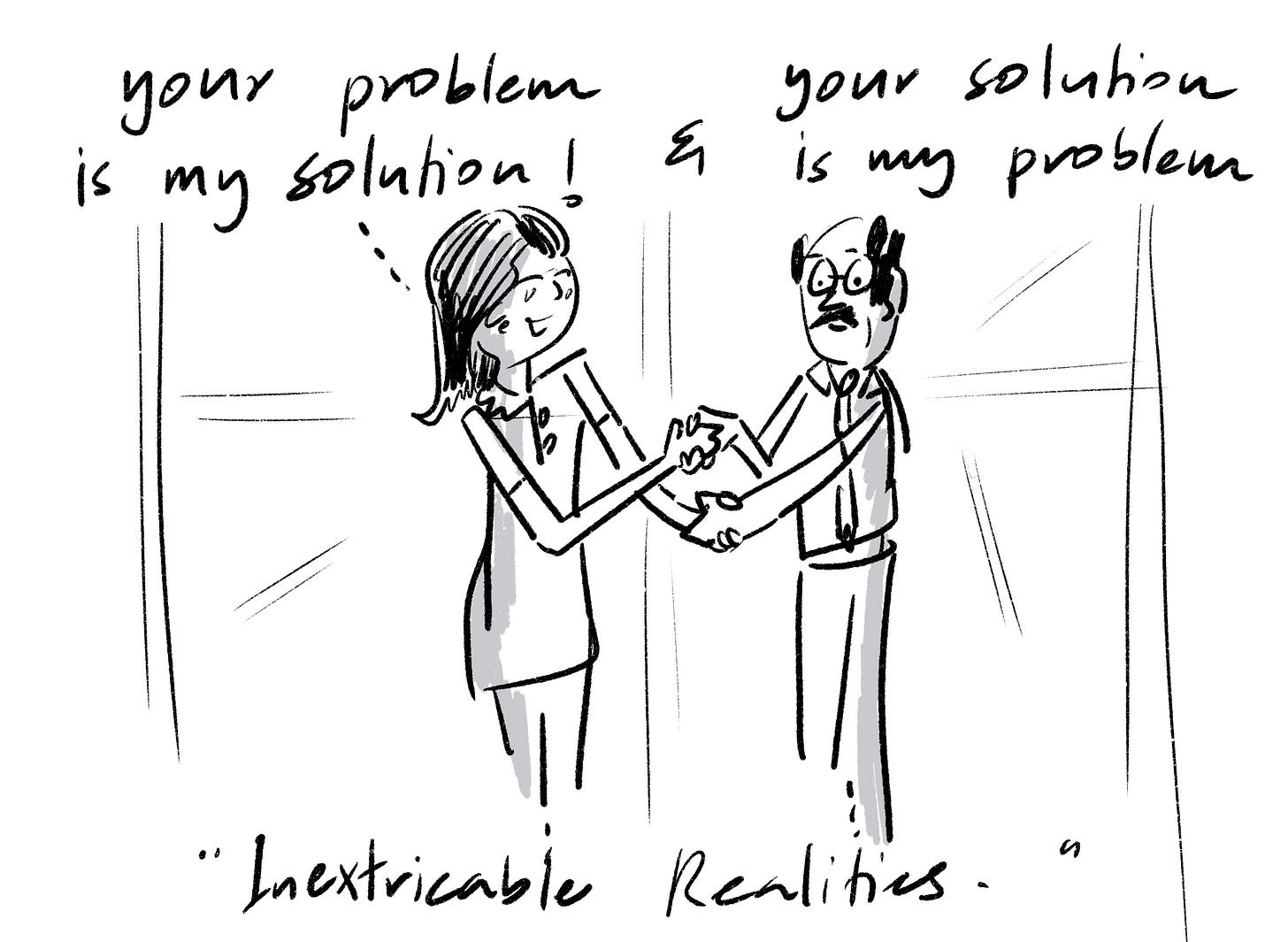

The Dual Equilibrium Challenge

In an ideal situation, an organization combines the best of both worlds: it preserves trustworthy relationships with partners, customers, beneficiaries while also not charging a premium for information asymmetries. That dual equilibrium is difficult to execute in the for-profit world. You could argue that an Amazon solves both problems - it sells like a supermarket and like a kirana store via its marketplace. But Amazon isn't loyal to the small businesses on its platform, and on occasion acts like a predator when it uses its access to sales information to duplicate the offerings of the most valuable marketplace sellers. If the choice is between making extra profits and letting a small business make that money, Amazon will likely choose the former.

This challenge exemplifies what we identified in our first essay as a "wicked problem" - one that resists straightforward solutions due to competing interests, complex interdependencies, and constantly evolving parameters. As we explored in our second essay on scale-bridging knowledge systems, there's a fundamental tension between local, relational knowledge and global, scalable systems. The traditional firm structure often forces organizations to choose between these approaches rather than integrating them.

Open Source as an Alternative Model

Open source takes a very different approach to production. It - literally - gives away the store for free, which means that programmer salaries have to be paid by someone else. In practice, that means large open source projects are either funded by corporations whose business model depends on having open source in its infrastructure or there's a way to monetize premium offerings on top of the open source base.

The open source approach embodies what our fourth essay called the "Ecological Programming Interface" (EPI) - a framework for connecting diverse systems through standardized methods of interaction. Open source creates trust architecture through transparent protocols, enabling collaboration while preserving local autonomy. It establishes what our second essay termed "scale-bridging knowledge systems," connecting intimate local knowledge (individual programmers) with global information systems (worldwide code repositories).

Common Source: A New Organizational Model

Somewhat surprisingly, civil society hasn't learned from the success of open source - of course, we don't make software for the most part, but can we think of organizational structures that have the openness and transparency of open source? One model we're playing with is what might be called 'common source.' If firms are like organs (such as the liver or the kidney) then common source is like the breath or blood - transporting nutrients to wherever they are needed. In simple terms,

Common Source = Open Source + People Sharing

i.e., the IP is both Free as in Beer and Free as in Freedom, and the people who are skilled in that IP are made available to the ecosystem at large.

The Wystem is Common Source by design.

This approach aligns with the wisdom-centric design principles we outlined in our third essay. Rather than focusing solely on efficiency (Simon's approach) or usability (Norman's focus), common source prioritizes trust, empathy, and justice. It recognizes that in complex systems, wisdom emerges not from control but from connection - from creating what our fourth essay called "trust architecture" through transparent protocols and clear feedback loops.

Common Source in Practice

Some of our work has been common source for a while - like when we have worked with partners such as Vaagdhara and SwitchON to organize citizen juries. These collaborations exemplify what our fifth essay on Flourishing Melukote demonstrated: the power of bringing together diverse stakeholders around shared goals while respecting their unique approaches and values.

In our citizen jury work, we've implemented what our third essay called "wisdom-centric design" - creating systems that not only work efficiently but actively promote collective wisdom, trust, and justice. By making our methodologies transparent and adaptable, we've enabled partners to apply them in their local contexts while contributing back to the collective knowledge base.

This approach differs significantly from the standard firm model, which treats knowledge as proprietary and staff as assets. Common source treats knowledge as a public good and people as autonomous agents who can move between contexts while carrying their expertise with them. It embodies what our sixth essay summarized as "local-global integration" - the practice of simultaneously thinking locally while acting globally, and thinking globally while acting locally.

Formalizing Common Source

We will talk about two more recent engagements in the next two Messengers, but so far, we have only been informal about common source. The next level of our commitment to common source is in making it available as an explicit offering. Ideally, that should look like:

Formalize the common source architecture and make it available as an EPI call.

This formalization would create what our fourth essay described as "standardized methods for diverse systems to interact." By structuring common source as an EPI call, we make it accessible to a wider ecosystem of partners and collaborators. This approach embodies the three pillars of wisdom-centric design we outlined in our third essay:

Trust Architecture: Common source builds trust through transparency and shared ownership

Empathy Integration: It recognizes and responds to diverse needs across contexts

Justice-Centered Design: It ensures equitable access to resources and knowledge

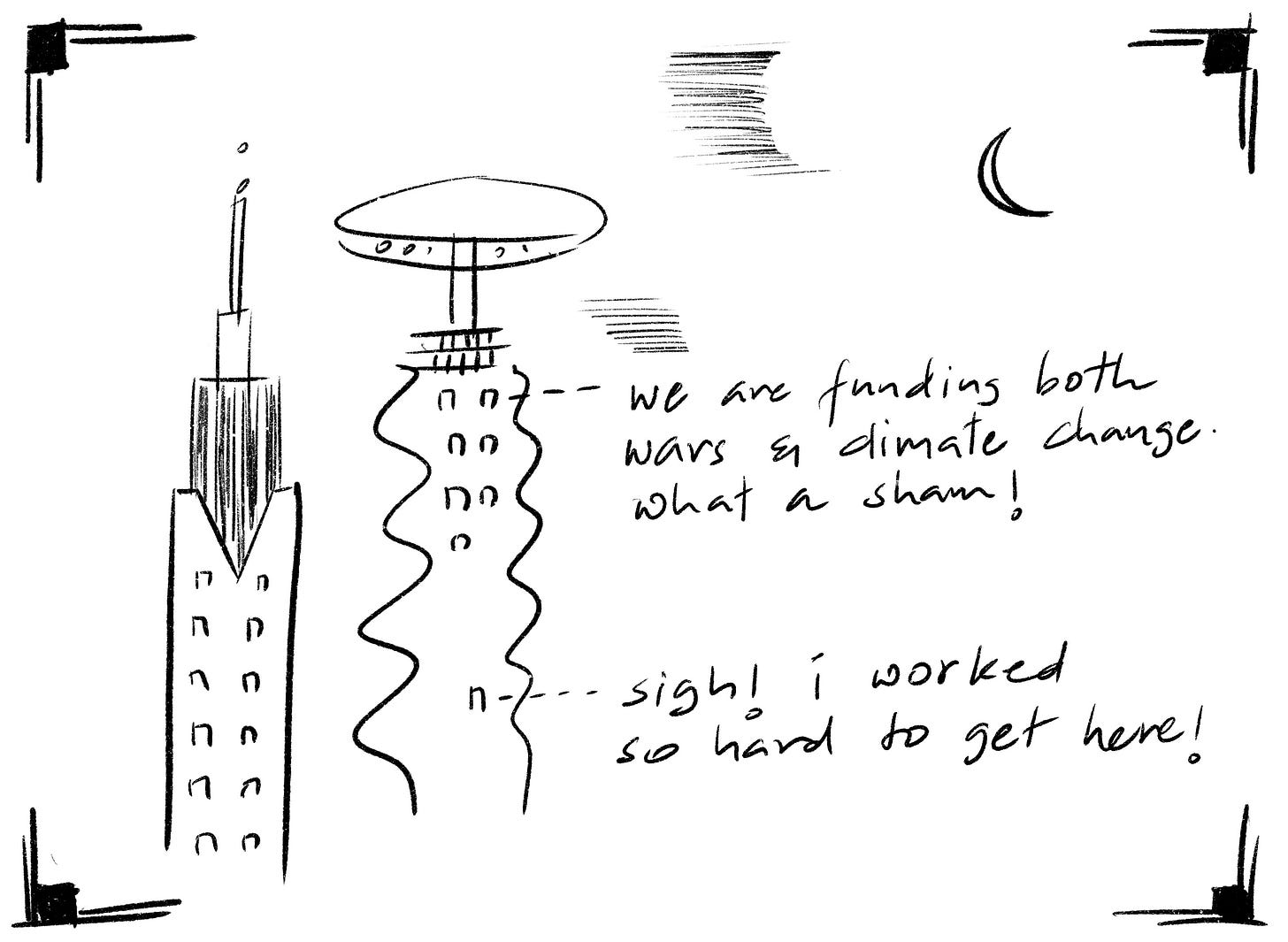

Why Common Source Matters for Wicked Problems

We think common source is particularly important for solving wicked problems (or Polycrises/Polyconflicts if you prefer that framing), since entangled challenges surely require fluid solutions that travel easily from one problem domain to the next. As we explored in our first essay, wicked problems resist traditional problem-solving approaches precisely because they span multiple domains and scales.

Traditional organizational structures, with their rigid boundaries and proprietary knowledge, struggle to address these interconnected challenges. Common source offers an alternative that embodies what our second essay called "scale-bridging knowledge systems" - approaches that connect intimate local knowledge with global information networks.

By making both intellectual property and human expertise freely available across the ecosystem, common source enables what our sixth essay summarized as "collective intelligence" - the ability of diverse stakeholders to collaborate effectively across boundaries. It creates conditions for what our third essay termed "wisdom-centric design" - systems that not only work efficiently but actively promote trust, empathy, and justice.

Conclusion: Toward a Common Source Future

As we continue to develop the Wystems Thinking framework, common source emerges as a key implementation strategy - a way to embody the principles we've explored throughout this series. From the scale-bridging knowledge systems of our second essay to the Ecological Programming Interface of our fourth, common source brings these concepts into practical reality.

By reimagining civil society organizations as common source entities rather than traditional firms, we create the conditions for addressing what our first essay called "wicked problems" - complex challenges that resist straightforward solutions. We enable what our fifth essay demonstrated in Melukote: multi-stakeholder collaboration that bridges local and global scales of knowledge and action.

The path forward involves formalizing this common source architecture, making it available as an explicit offering through what our fourth essay called the "Ecological Programming Interface." This approach will enable civil society organizations to maintain their unique identities and approaches while participating in a larger wisdom-generating ecosystem.

In a world facing increasingly complex, interconnected challenges, common source offers a promising alternative to traditional organizational models - one that embodies the Wystems Thinking principles we've explored throughout this series. By sharing both knowledge and expertise freely across the ecosystem, we create the conditions for the collective wisdom needed to address our most pressing problems.

From Climate Recipes, Bhitarkanika edition on coastal landscapes of Odisha