Living with Others, Part 2: The Multispecies Studio

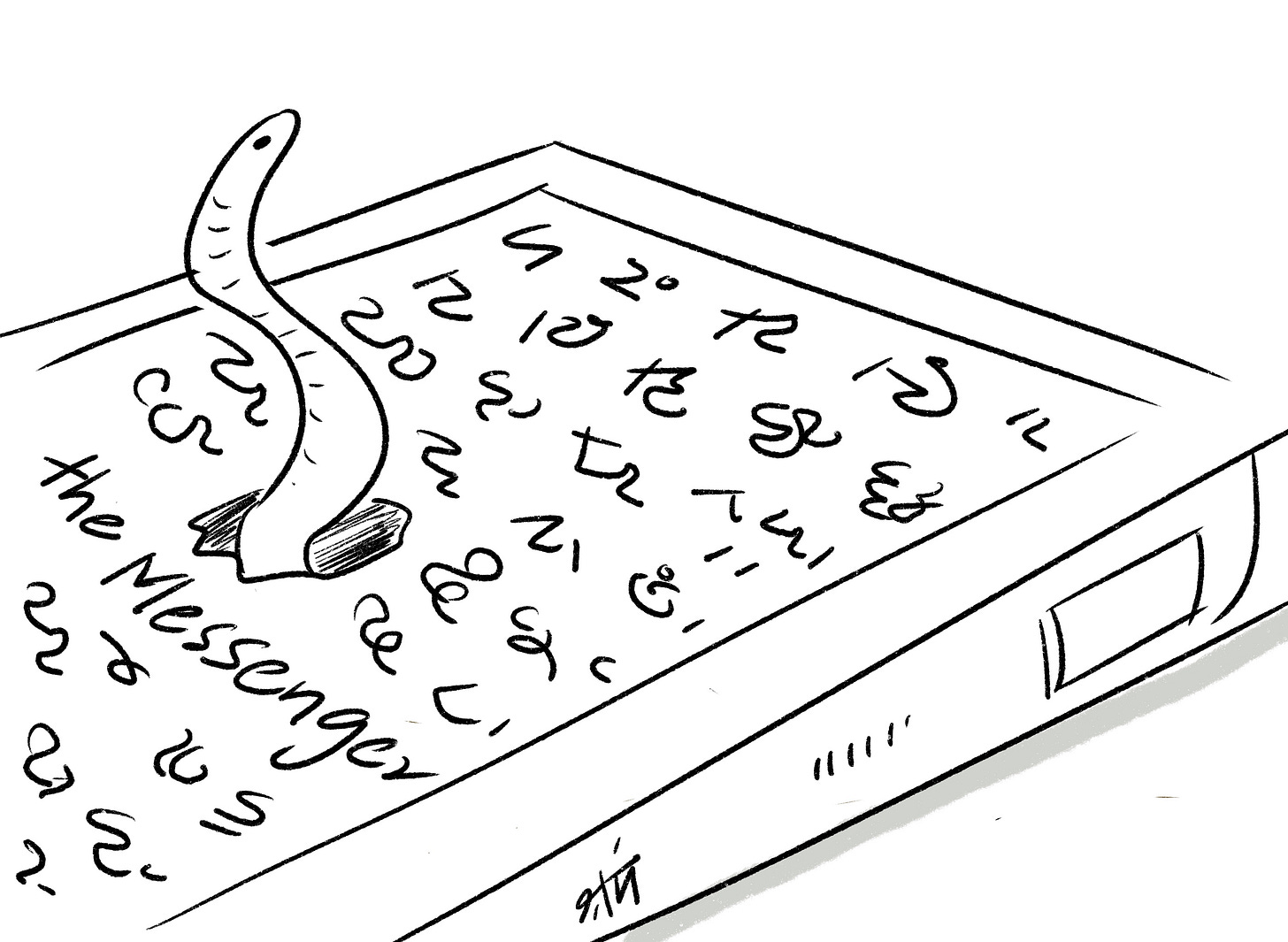

Over the past few years, we have spent a lot of time thinking about the idea of flourishing - of people, communities, and of places. What if we were to expand the idea of communities and places in this framework to include non-human life? This Messenger is the second in a series that processes this idea of multispecies flourishing as it applies in our work in cities, villages and forests; and as it finds expression in different ways among us - within our own multispecies working group, and beyond.

The first essay in this series:

Living with others: On Multispecies Wisdom, Part 1

Anyone walking the sidewalks of Bangalore or Mumbai is bound to encounter a cow or a dog minding its own business without a human in tow. Free-ranging animals dot our urban landscape, even when they are eventually bound to a human being. Some consider our more than human cities a sign of backwardness. Others take it as a sign of an advanced civilization…

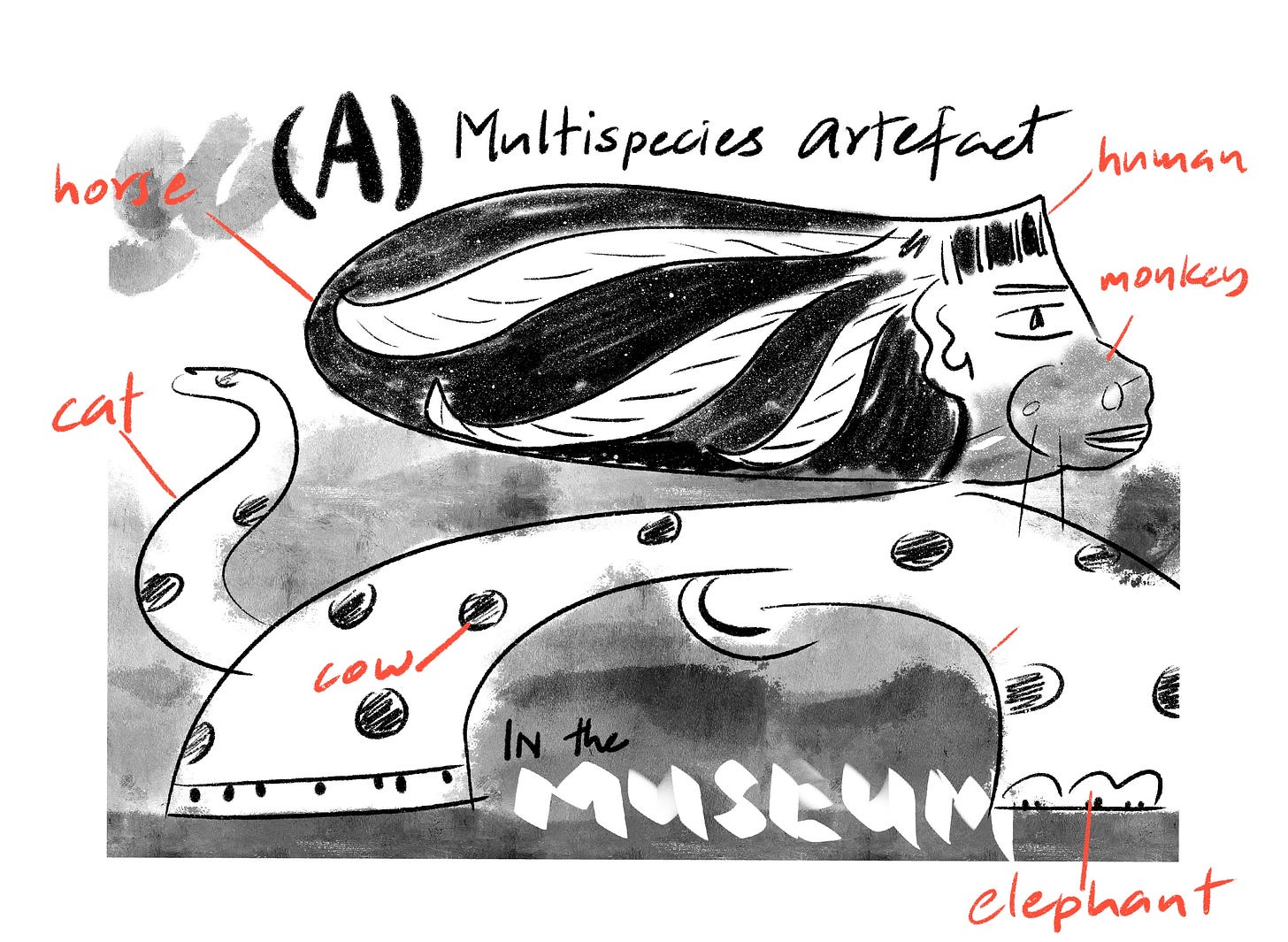

The idea behind this piece is to present multispecies ethnography as a methodology that can be valuable in our Indian context where attentiveness to the range of living beings that occupy the same space can quickly reveal relationships that are not adequately captured by scientific designations such as “predator-prey relationships” or “invasive/native species”, nor for that matter, by more general purpose terms such as “human-animal conflict” or “pest”. These terms can work to conceal an entire history of coevolution, of sharing space, of histories of migration, of individual relationships... The work of multispecies ethnography then lies in reading such material shared through anecdotes, stories, archives and myths, together with emerging insights from disciplines such as ecology, biology and ethology to work towards finding collaborative ways of living together well as flourishing, multispecies communities.

It is important to state at the outset that, taken on its own, flourishing connotes nothing but positive associations - of thriving, growing, blossoming. But to quote the fungal researcher Merlin Sheldrake, “collaboration is an alloy of cooperation and conflict”. So the question of whose flourishing, and at whose expense, are central concerns for us. What the multispecies studio could offer then is a space to orient oneself ethically in relation to the particular context and situation rather than to a fixed conservation or humanist or animal welfare ideal.

Aside on “place-based approach”: Recently at our office in Bangalore, we were thinking about how to talk about or work in field settings and

learned that the Hindi word for ecology is पारिस्थितिकी, a derivative of the word for “situation”. That’s an interesting way of conveying what we’re trying to do here – situationalism!

This kind of explicitly multispecies framing has emerged organically though our field interactions in a variety of settings, and has helped us better understand what is at stake – in our engagements with farmers in Coimbatore who must contend with crop raids by elephants, peacocks and deer on a regular basis; in conversations with Pourakarmikas in Shantinagar who take special care each morning to dispose of glass waste to protect hungry street dogs; and through our work in the mangrove forests of Bhitarkanika, where the mighty saltwater crocodile is a constant presence, in its basking glory or as lurking threat.

These experiences have convinced us of the importance of telling complex, compelling, and urgent stories of multispecies communities that continue to share space and live together. Our effort in the multispecies studio will be to make use of different tools, such as art, ethnography, and emerging technologies, to investigate the different kinds of threads – commensal, emotional, spiritual, legal, economic – that tangle and bind together heterogenous, multispecies communities “without either harmony or conquest”, to use Anna Tsing’s brilliant turn of phrase.

The Myth of the Virgin Forest

Rather than thinking of ecosystems as closed circuits, we would do well to appreciate the constant coming and going of various living beings across, and without regard for, the fanciful borders of city limits or protected area forests. This means dismantling the notion of the pristine landscapes, untouched forests, and equally, of urbanised settlements as the sterile and rightful domain of humans alone. We are constantly being reminded that these visions of stasis and enclosure do not, and indeed, have never held water. Newer scientific work on recombinant ecologies has begun to recognise this porosity across ecosystems. We now dwell on this idea of porosity.

In next week’s Messenger, we will speak more about our work on India’s urban street dogs, but for now, a conversation we had with an eminent rabies prevention and vaccinology expert contained an interesting turn of phrase that is relevant here. Referring to a tragic incident of a dog mauling a child in Kannur, he said, “you see, all this talk about ecology, it's not only an environmental issue.” He was referring to the city’s significant Muslim population, who largely tend to care for cats rather than dogs as companion animals. As a result of this, with fewer human caregivers who provide for street dogs in the Muslim-dominated parts of the city, feral dogs from the neighbouring forested areas had started to enter these parts to access available resources and were wreaking havoc. “Literally with my own eyes, I saw foxes, wild animals roaming the street” he said incredulously.

As a framework that expresses environmental and social factors in tandem, this explanation is attuned to the canine capacity to exploit a vacant ecological niche in the city; to the effects of consistently shrinking mangrove forests in areas surrounding Kannur which provide resources to dogs and other wild inhabitants; and to a specific aspect of cultural life in the region that has resulted in a reduced population of urban adapted dogs that are socialised to live peacefully alongside humans. As evidenced here, a multispecies approach could be used to find ways to understand problems by adopting seemingly incompatible frames of reference together. Again, the idea is not to have a diversity of perspectives for its own sake, but to address a set of questions.

Rather than sticking to a single ecosystem – urban or mangrove or shola grasslands – we believe our mission of relaying stories with multispecies protagonists, and of developing a politics grounded in specific contexts will be best served by a collaborative ethic and a comparative, ecological approach as it provides a way to trace contingent and uneven porosities across our different areas of work in agroecology, livelihoods and waste management. For instance, what makes dogs so adaptable to urban environs and how has urban waste shaped their scavenging habits? How do the brackish water habitats of prawns and shrimp relate to shrinking mangrove forest cover? Deeper engagement with the capacities and perceptual worlds of different species can offer altered vantage points to apprehend relations across time and space, and in excess of anthropocentric sensibilities.

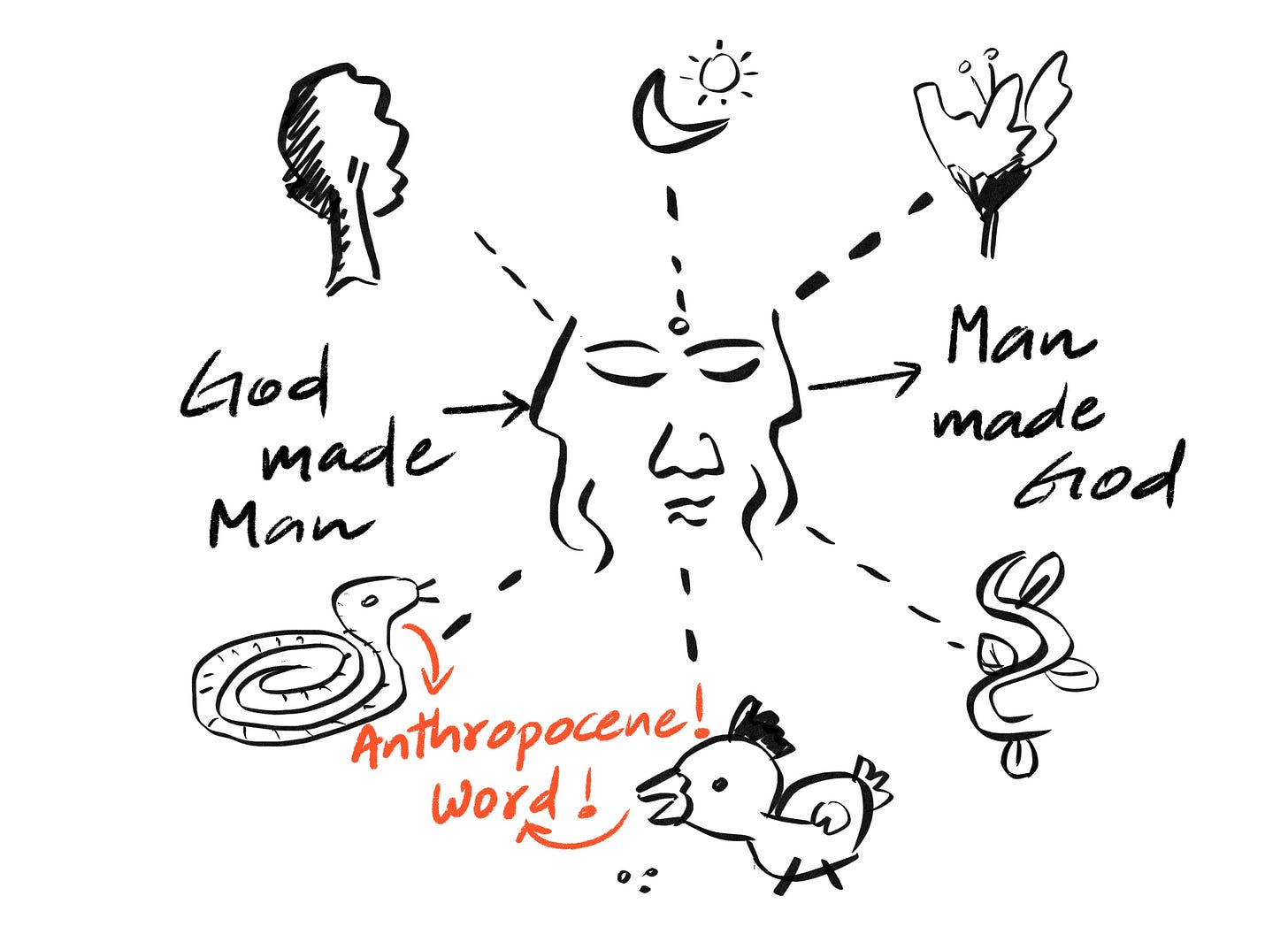

Building upon our work with climate vulnerable communities such as Adivasis in the Vagad region, farmers across India, and residents of coastal Orissa, we seek to intervene by centering questions of inequality and environmental justice, while also recognising the power of non-humans to act in ways that matter. At the heart of this effort, then, is a move toward a more considered understanding of what is at stake in how we choose to view ourselves in relation with the world around us.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll provide some insights that have emerged from our ongoing narrative building work on urban India’s street dogs, and our longer term plans for ethnographic work in the coastal mangrove ecosystem of Bhitarkanika. What might it take to unsettle the anthropocentrism lodged so centrally in the idea of community life, and work towards a more multispecies framing that is receptive to the constant comings and goings of various living beings with particular capacities and attunements. How can we tell stories of these meshworks of living beings, which recognize that agencies, subjectivities, and even cultures are distributed across species boundaries; and which recognise other-than-humans as protagonists in their own right rather than merely the supporting cast?

Enter the Multispecies Studio

Climate Recipes

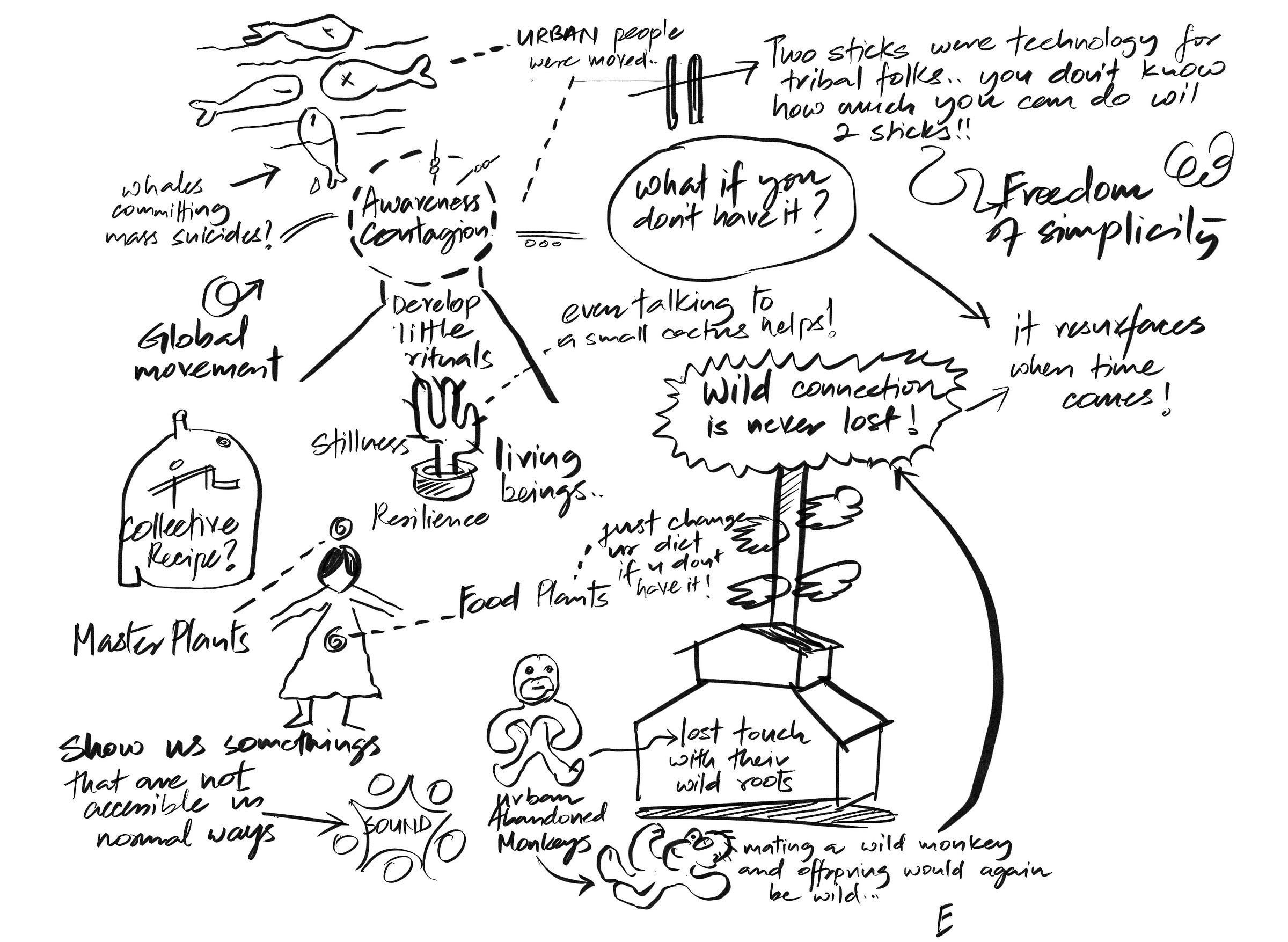

“Communicating horizontally with non-human entities” - Enit Maria, Goa Edition

People are increasingly becoming anthropocentric, where they are willing to consume nature and not befriend it. It’s a one-way street. We should reestablish a horizontal camaraderie with the natural world and non-human species. It is a method to reorient towards the ground beneath, rather than the aspiration to look up. Humans also need to understand that the earth is trying to tell them something about the wildfires and the floods. We are far from listening to it while we objectify and categorize nature. We are at the edge where we have to learn how to approach non-humans in their terms.