Living with others: On Multispecies Wisdom, Part 1

Anyone walking the sidewalks of Bangalore or Mumbai is bound to encounter a cow or a dog minding its own business without a human in tow. Free-ranging animals dot our urban landscape, even when they are eventually bound to a human being. Some consider our more than human cities a sign of backwardness. Others take it as a sign of an advanced civilization.

Friend or foe, nonhuman lives are entangled with ours, and not just quasi-domesticated species such as ruminants and canines, but also birds and reptiles and insects and, of course, the vast diversity of grasses and shrubs and trees. They too inhabit the same spaces as we do, and for the most part, their cohabitation is so unremarkable as to find mention only in first world travelogues. That’s the multicellular menagerie - we aren’t even considering the vast array of unicellular life that lives inside and around us. But times are a changing. Like in so many other instances, the Anthropocene is raising the profile of multispecies spaces, turning them into models of how we might live on this planet with others.

Over the last few decades, at least five emerging lines of work have taken the nonhuman world into active consideration:

The tragedy of ecosystem collapse, of the sixth great extinction. And of the immense cruelty of factory farming and animal rearing for food and other human needs. Animals and plants everywhere are under stress. How can we turn their suffering into flourishing?

Progress in the cognitive sciences which has revealed the extent to which non-human beings possess minds. Including plants, at least according to some researchers! If the ‘mind’ is what makes us human, then it turns out there are many creatures like us.

Our increasing awareness of being inextricably entangled with the web of life - it’s not just that we depend on other beings, it’s that we are those other beings. The bacteria in our gut keep us alive, and we literally breathe the excreta of unicellular photosynthesis. There’s no US without THEM.

New machine learning technologies that might help us see the world as our fellow creatures see it (seeing being a stand-in for all sensory engagement), and potentially communicate with them.

Anthropologists and other environmental humanities researchers who are recognizing the non-human worlds next to the human worlds they have typically studied.

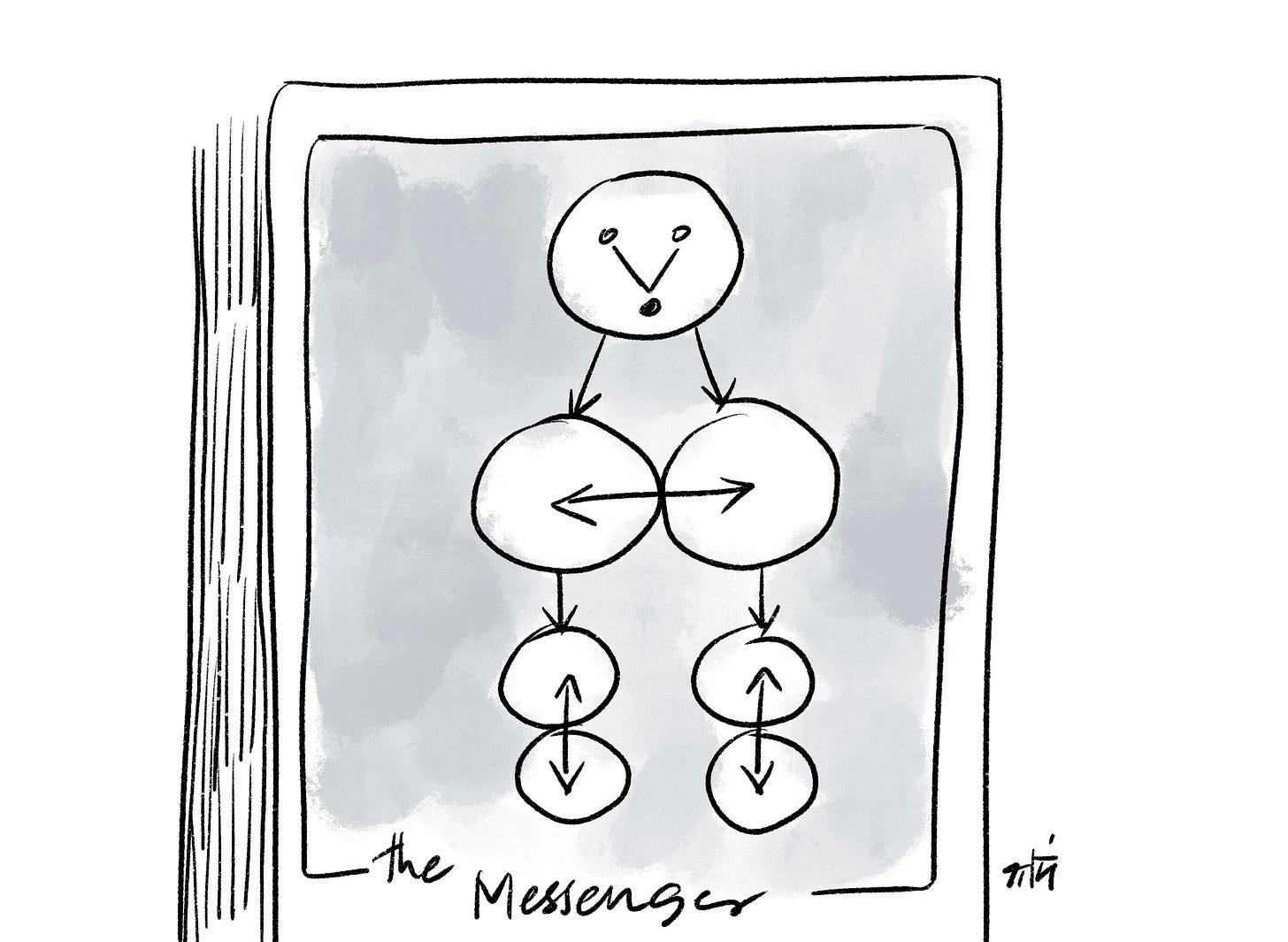

These strands of inquiry intersect occasionally, but mostly, the ecologists, the neuroscientists, the social scientists and the technologists live in their own disciplines. Our goal is to synthesize these strands into an exploration that borrows freely from these four lines of work. We are intellectual glue, providing concepts and methods that freely travel from one discipline to another. If that’s too abstract a claim, we have two innovations on offer:

Synthetic philosophy as the connective tissue of disciplines, i.e., not as abstract theory that comes before scientific inquiry, but as ideas and concepts that transport scientific disciplines from one corner of the academic universe to another. Here’s an inspirational quote: “I think the strength of this kind of philosophy is to find insights that you don't find within disciplinary boundaries, or that are more difficult to find.”

Design and art as a common medium of representation, making the invisible visible, the tacit explicit and realizing plausible futures. A common “presearch” framework that disciplinary actors (scholars, conservationists etc) can shape further as they see fit. Note: Presearch is the employment of design as a mechanism to generate ideas, theories, and broadly, to prototype knowledge creation.

Ready or not, we are in the Anthropocene, a period marked by the significant impact of human activities on the Earth. This era compels us to rethink our view of the world and our role within it. Philosophy (and whenever you read the term ‘philosophy’ in this essay, just add design + art to it to complete the trio) now faces the crucial task of understanding not just humans, but all life forms, recognizing the deep interconnectedness of all beings on our planet.

Understanding Our Current Age: The Anthropocene

A few months ago, we wrote about the task of philosophy in the Anthropocene. You can read the two articles below to get a taste:

Apprehending our Age

It's a new year, and it's been four turns around the sun since Socratus opened doors. Way back when we promised we will become the midwives of collective wisdom. We are not there yet, but we do have a better understanding of our role in evoking the wisdom of the world.

Apprehending the Anthropocene

The Indian Anthropocene What age do we live in? Some might say: the Information Age. Others might say: the Third Industrial Age. And let's add the 'Age of Globalization' for good measure. All right answers, but arguably, the most appropriate answer to the question is: we live in the Anthropocene.

Our multispecies work is the first step we are taking towards apprehending the anthropocene. In today's world, philosophy must grapple with the profound implications of human influence on the Earth. It's no longer just about studying human existence in isolation; it's about comprehending the intricate web of life that connects all living things. We need a radical shift in perspective, one that sees human society as part of a vast network of life, rather than separate from it. As we have said before:

Nothing in society makes sense except in the light of the planet.

Expanding Our Understanding

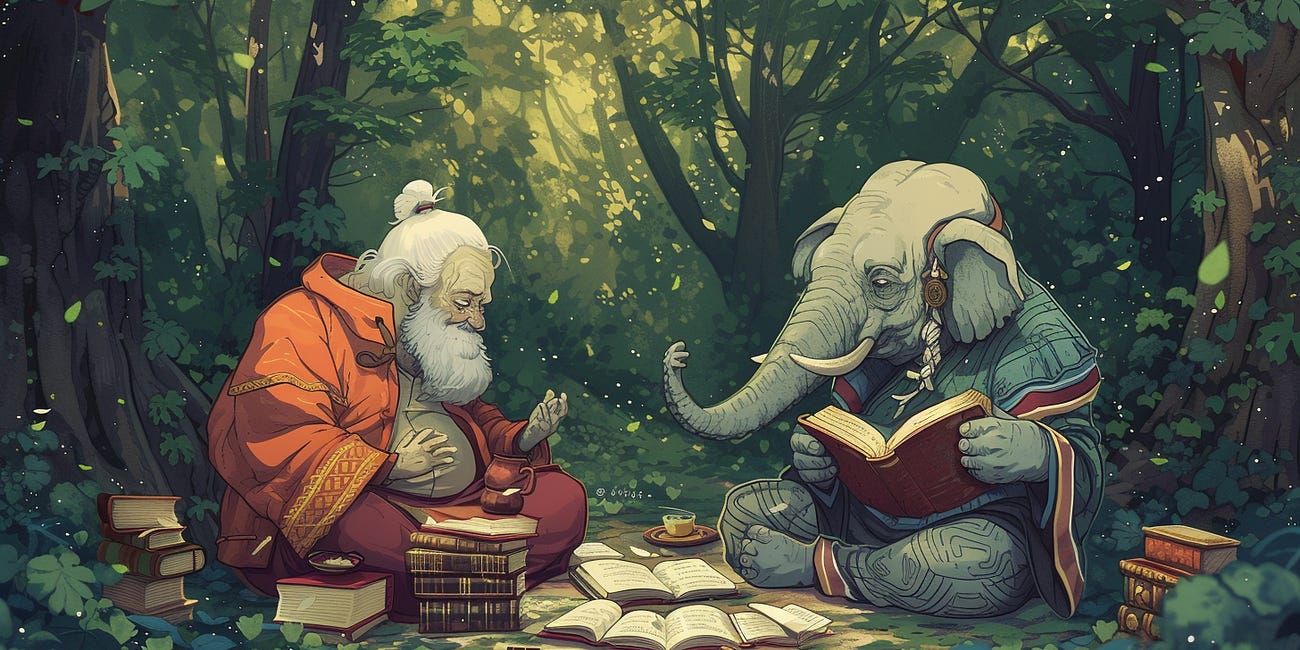

Every creature on Earth, not just humans, plays a role in shaping our planet. Philosophical thought must now embrace the perspectives and wisdom of all cultures and species. Animals like apes, elephants, whales, and octopuses possess unique intelligences and ways of interacting with their environments. By considering their insights, we gain a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics of our world. This is where new technologies of connection can help us bridge the divide between species.

Our long-term goal is to learn from the many species that share our planet, using technology to help us understand and connect with them. This approach moves us beyond human-centered thinking to a more inclusive and holistic view of the world. By embracing the wisdom of all beings, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the intricate dynamics of life on Earth and our place within it. This integration of philosophy, design, and art helps us explore and understand the complex relationships between all forms of life on our planet.

That’s still a long ways away! Baby steps first. Over the next few weeks, we will share some of our work on how we are bringing a multispecies perspective to our work at Socratus, including human-dog relations in cities and human-crocodile co-existence in Odisha. And then we will write about how we are going back to Shaktiville.

Introducing Shaktiville

The Strange and the Familiar You’ve probably heard a thousand stories that begin with ‘once upon a time.’ Can you name one story that begins with ‘once upon a place’? Why does time play such an important role in mythmaking and not place? Thanks for reading The Messenger! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

Climate Recipes

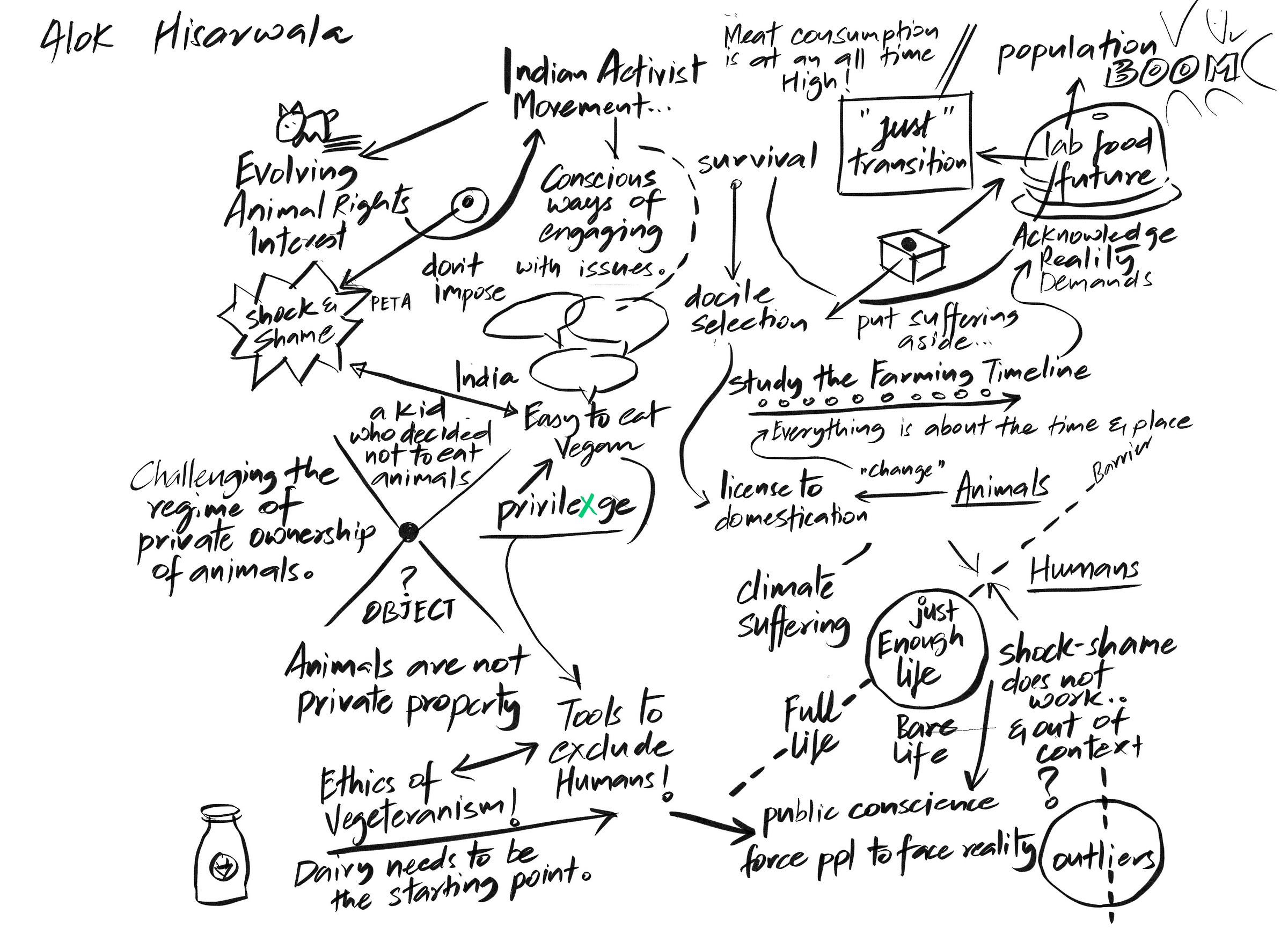

“Animals are not private property” - Alok Hisarwala, Goa Edition

The legal regime of animal rights has no robust regulations for domestication and punishments for animal brutality. We should acknowledge the animal’s desire to live and create goals for their rights. The alternatives of veganism that abstain from the commodity status of the animals are not homogenous solutions to highly interdependent habitats. While the current generation is sensitive to the killing of animals for meat purposes, they are not aware of their continuous torture by the dairy industry, which keeps them captive. Creating public awareness about these realities is crucial. We need to inflect instances where people realize their food and lifestyle choices are creating large-scale suffering and leading to climate disasters.

A note on the role of technology - This is more of a promissory note, but of late there’s much excitement that machine learning tools can help bind different creatures together and allows us to better comprehend the Earth and its inhabitants. The philosopher, Thomas Nagel, wrote a famous paper called “What is it like to be a Bat” where he argued that the inner world of a bat is forever closed off to us. The excitement around project CETI opens up the possibility that the worlds of other creatures can be translated into ours. It’s not the same as experiencing the original, but it’s a lot better than having no clue whatsoever!

See you next week!