Wystem Architecture 4: Philosophy as Infrastructure

This is the last essay in the Wystem Architecture series. The Messenger is taking a break and will be back in a few weeks.

When Marx declared that "philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it," he wasn't abandoning philosophy but calling for a new kind of philosophical practice—one that bridges reflection with action, theory with design, individual wisdom with collective capability. We don’t have to be Marxists to take that claim seriously!

Today, as we face challenges that defy simple solutions—climate change, artificial intelligence governance, rising inequality—we need exactly this kind of transformative philosophical thinking. But we also need something Marx couldn't have anticipated: technologies that can scale trust and connection across vast networks of strangers. The question becomes how philosophy can inform the design of these crucial technologies, and how these technologies can, in turn, democratize philosophical wisdom.

The Architecture of Trust

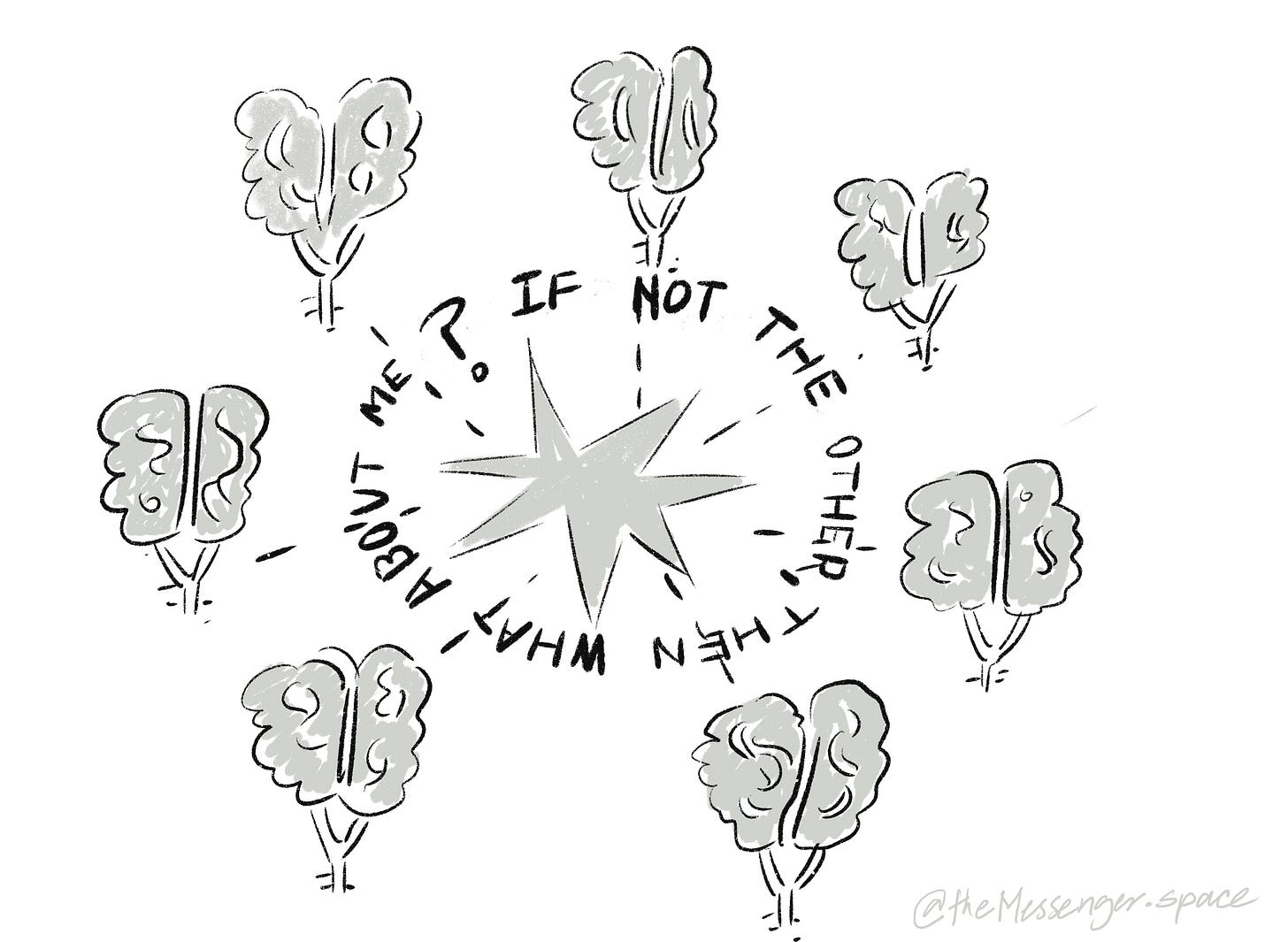

Trust is the invisible infrastructure of human cooperation. In small communities, trust emerges through repeated personal interaction—I know you, you know me, and our reputations are intertwined within a web of relationships. But modern life requires us to cooperate with strangers, sometimes on the other side of the world. This creates what we might call the "scaling problem" of trust: how do we maintain the accountability and reciprocity that makes trust possible when we can no longer rely on face-to-face interaction?

Money represents perhaps our most successful technology of trust. When I present a piece of paper at a store and walk away with a bar of soap, something magical has occurred—a stranger has trusted that this symbolic token represents real value, backed by institutions neither of us directly control. Nation-states function similarly, allowing citizens to access services and expect protection across vast territories through shared institutional frameworks.

Yet these institutional technologies of trust, powerful as they are, have significant limitations. Money commodifies trust, turning it into a transaction rather than a relationship. Nation-states create inclusion through exclusion, defining citizenship against otherness. Both can be weaponized—money concentrates power, states can become instruments of oppression. We need technologies that create what we might call "wisdom-centric connections," systems that don't just enable cooperation but actively promote understanding, empathy, and collective intelligence.

The Promise and Peril of Digital Connection

Social media platforms promised to solve the scaling problem of trust by connecting everyone to everyone else. In many ways, they succeeded: people across the globe have formed meaningful relationships through these technologies, sharing knowledge, providing support, and building communities that transcend geographical boundaries.

But as we've learned painfully over the past decade, these same technologies have been twisted for malicious purposes. What was designed to connect has often fragmented; what was meant to build trust has frequently eroded it. Social networking platforms have become instruments of manipulation, amplifying anger and division rather than understanding and cooperation.

This failure points to a crucial insight: there is no such thing as a pure technology whose purpose cannot be corrupted. The challenge, therefore, is not to create perfect technologies but to design systems that resist corruption and misuse. The answer may lie in understanding what makes traditional forms of connection resilient and translating those principles into digital architectures.

Face-to-face communities have built-in accountability mechanisms. When you know someone personally, when your reputation depends on your behavior within a visible community, you're less likely to abuse trust. The question becomes: how do we build these accountability mechanisms into technologies of connection?

A live synchronous touching network.

When you touch the screen, it tells you how many people are touching at the same time.

Philosophical Practice for a Connected World

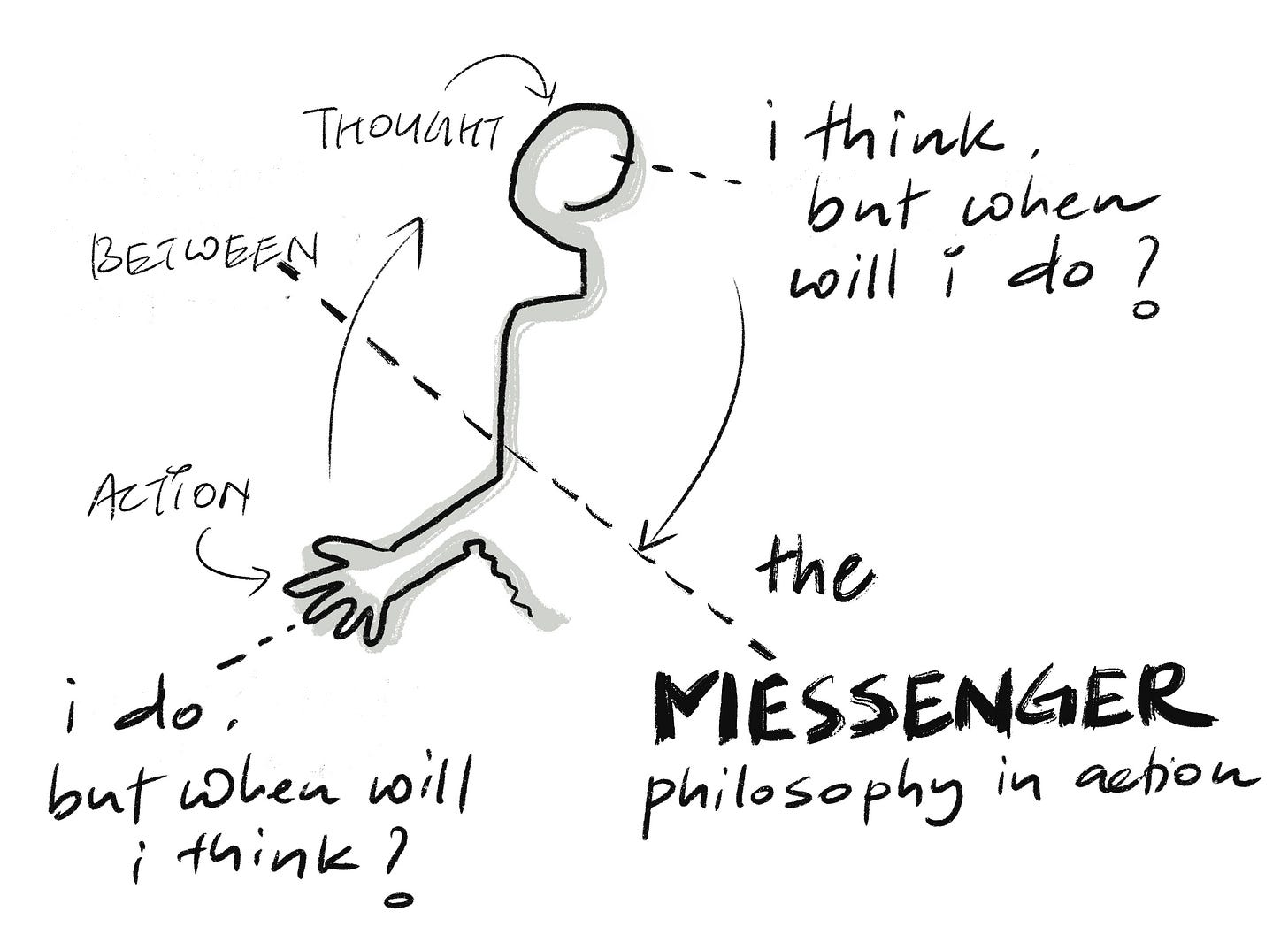

This is where philosophy becomes essential—not as abstract theorizing but as practical wisdom applied to design challenges, and in particular, as infrastructure for social change, of which ‘connection patterns’ are an important example - about which Gautam John wrote eloquently a few weeks ago. This transformation of philosophy as patterns of connection - and infrastructure more generally - requires new kinds of philosophical practitioners who can bridge traditional divides between theory and action, local knowledge and global systems, individual insight and collective capability.

Consider four archetypal roles essential for building technologies of trust and connection:

The Worldmaker helps us imagine alternative realities—courts where rivers can file suits against polluters, cities where other species have recognized homes and rights. Without this capacity to envision different possibilities, we remain trapped within existing paradigms.

The Elephant sees wholes rather than parts, recognizing patterns and connections across seemingly disparate domains. While most experts focus on specific aspects of complex systems, the Elephant philosopher seeks broader understanding essential for addressing interconnected challenges.

The Architect designs new frameworks for collective action and thought, creating not just physical spaces but institutions and systems that help people collaborate more effectively. They understand that changing the world requires changing the structures that shape how we think and act together.

The Connector operates as a philosophical ecologist, mapping relationships between different domains of knowledge and practice. They recognize when differences matter and when commonalities should be emphasized, bringing together previously separate fields of understanding.

Together, these philosophical practitioners create what we might call "trust architecture"—frameworks that make connection meaningful rather than merely efficient. They help ensure that new technologies serve genuine human and ecological needs rather than simply optimizing for engagement or profit.

Common Source: An Alternative Model

Traditional organizational structures force a false choice between local, relational knowledge and global, scalable systems. Firms exist to solve specific problems by creating internal hierarchies that reduce transaction costs, but this model treats knowledge as proprietary and people as assets rather than collaborative agents.

What if we could integrate both local responsiveness and global knowledge sharing? "Common Source" offers an alternative approach, treating both intellectual property and human expertise as public goods that can flow freely across contexts while maintaining accountability through transparency and shared ownership.

Unlike traditional firms that function like organs in a body—each with a specific, contained function—common source operates like blood or breath, transporting nutrients and knowledge wherever they're needed most. This creates natural accountability mechanisms similar to face-to-face communities but scaled through digital transparency. It embodies genuine reciprocity through shared knowledge and expertise, encouraging investment in relationships rather than frictionless, commitment-free interaction.

Democratizing Philosophical Wisdom

Perhaps most importantly, common source enables what we might call "wisdom flows"—knowledge and insight flowing not just from experts to citizens but between citizens themselves as they engage with shared challenges. This principle finds practical expression in citizen juries, where ordinary people become practical philosophers through structured deliberation about issues affecting their communities.

The jury model demonstrates how philosophical capabilities—systems thinking, ethical deliberation, collaborative problem-solving—emerge naturally when people are given appropriate spaces and support to tackle complex challenges together. Jurors learn to step back from immediate self-interest, consider multiple perspectives, weigh evidence carefully, and work toward solutions that balance competing needs.

This represents a fundamental shift from philosophy as elite practice to philosophy as democratic capability. Rather than wisdom raining down from experts to people on the street, citizen juries show how communities can develop collective wisdom through structured engagement with shared problems. They become philosophers not through abstract theorizing but through the lived experience of working together to understand and improve their shared world.

Conclusion: Philosophy as Infrastructure

The journey from Marx's call to change the world to contemporary experiments in citizen deliberation reveals philosophy's potential as practical infrastructure for trust and connection. By combining the rigorous thinking of traditional philosophy with the design sensibilities needed to build new institutions, philosophical practitioners can help create technologies that don't just enable cooperation but actively cultivate wisdom.

This work is urgent. As we face unprecedented global challenges requiring coordination across vast networks of diverse stakeholders, we need new forms of philosophical practice that can bridge individual insight and collective action, local knowledge and global systems, theoretical understanding and practical implementation. The technologies of trust and connection we build today will shape humanity's capacity to navigate complexity and uncertainty for generations to come.

The question is not whether we need philosophy to change the world, but what kinds of philosophical practice can help us build the wisdom-centric connections essential for addressing our most pressing challenges. The answer lies not in choosing between interpretation and transformation, but in recognizing how thoughtful interpretation can inform transformative design—and how transformative practice can, in turn, deepen our understanding of what it means to live and think together in an interconnected world.