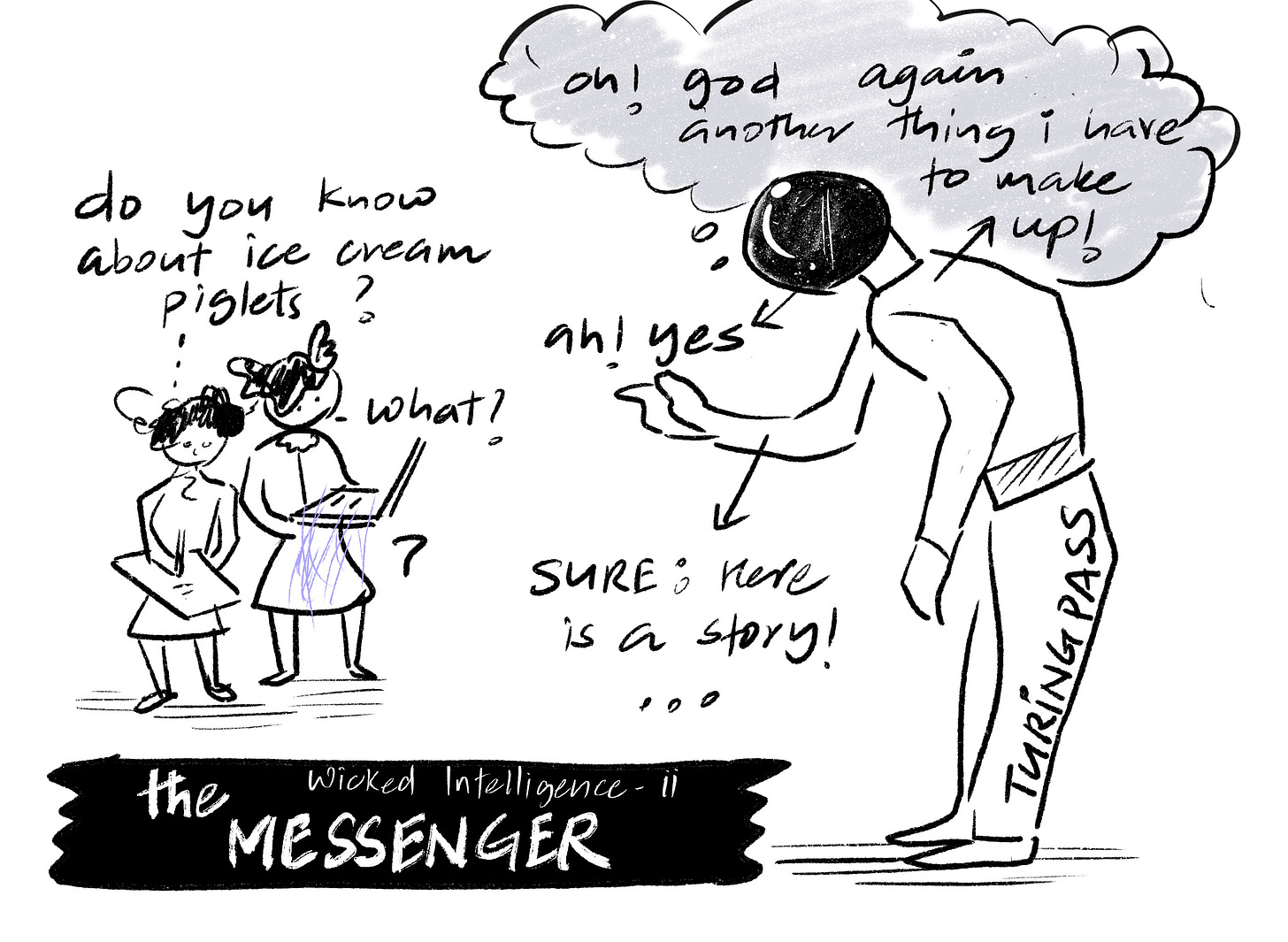

Wicked Intelligence, Part 2

Knowledge Work

AI automates cognitive labour. That's the bottom line. So much of white-collar work is writing reports, making presentations, convincing others why they should give you money. This is especially true if you are a civil society organisation. And the worry is that all of this can be done at a higher quality and at zero price by AI.

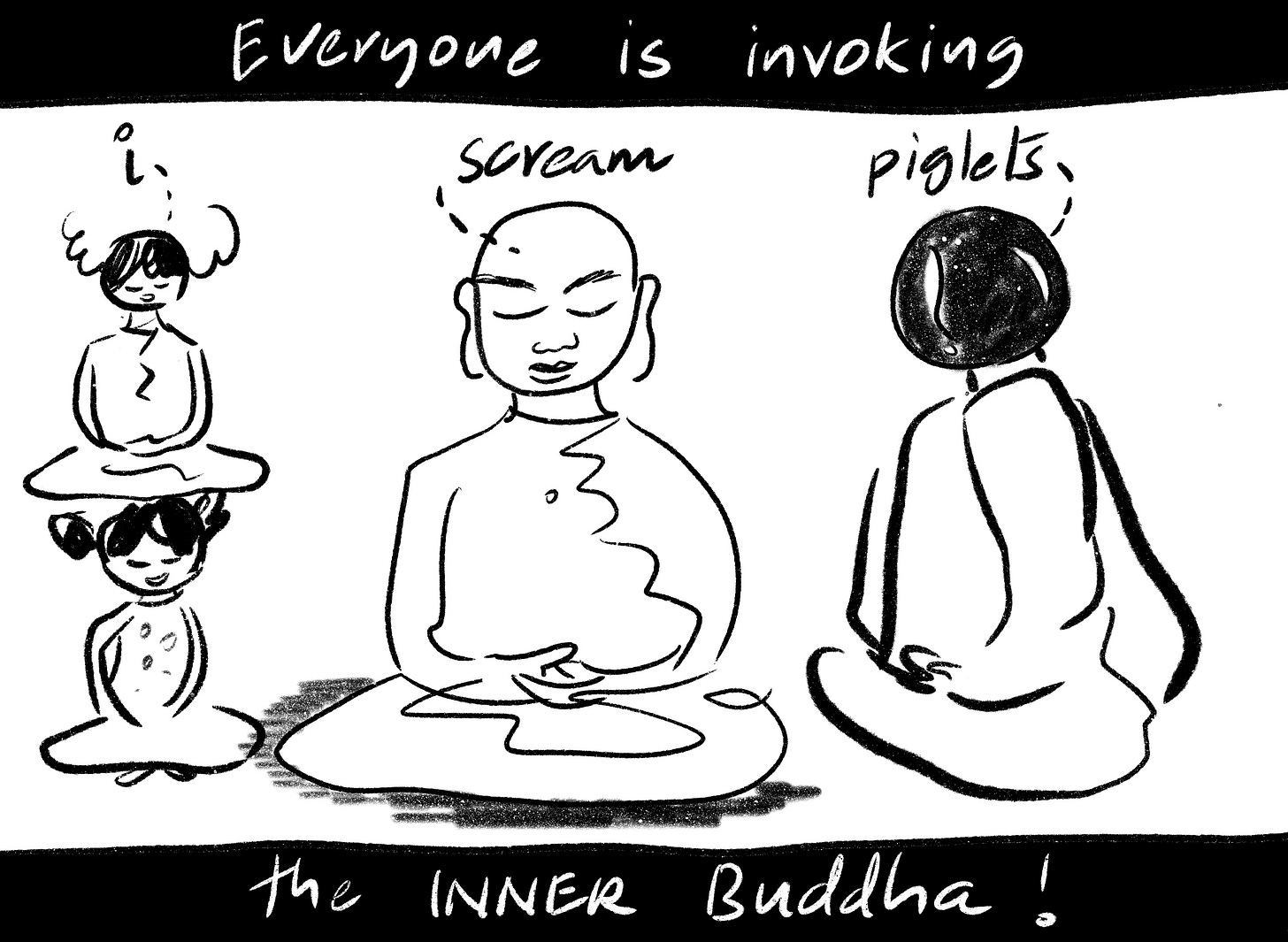

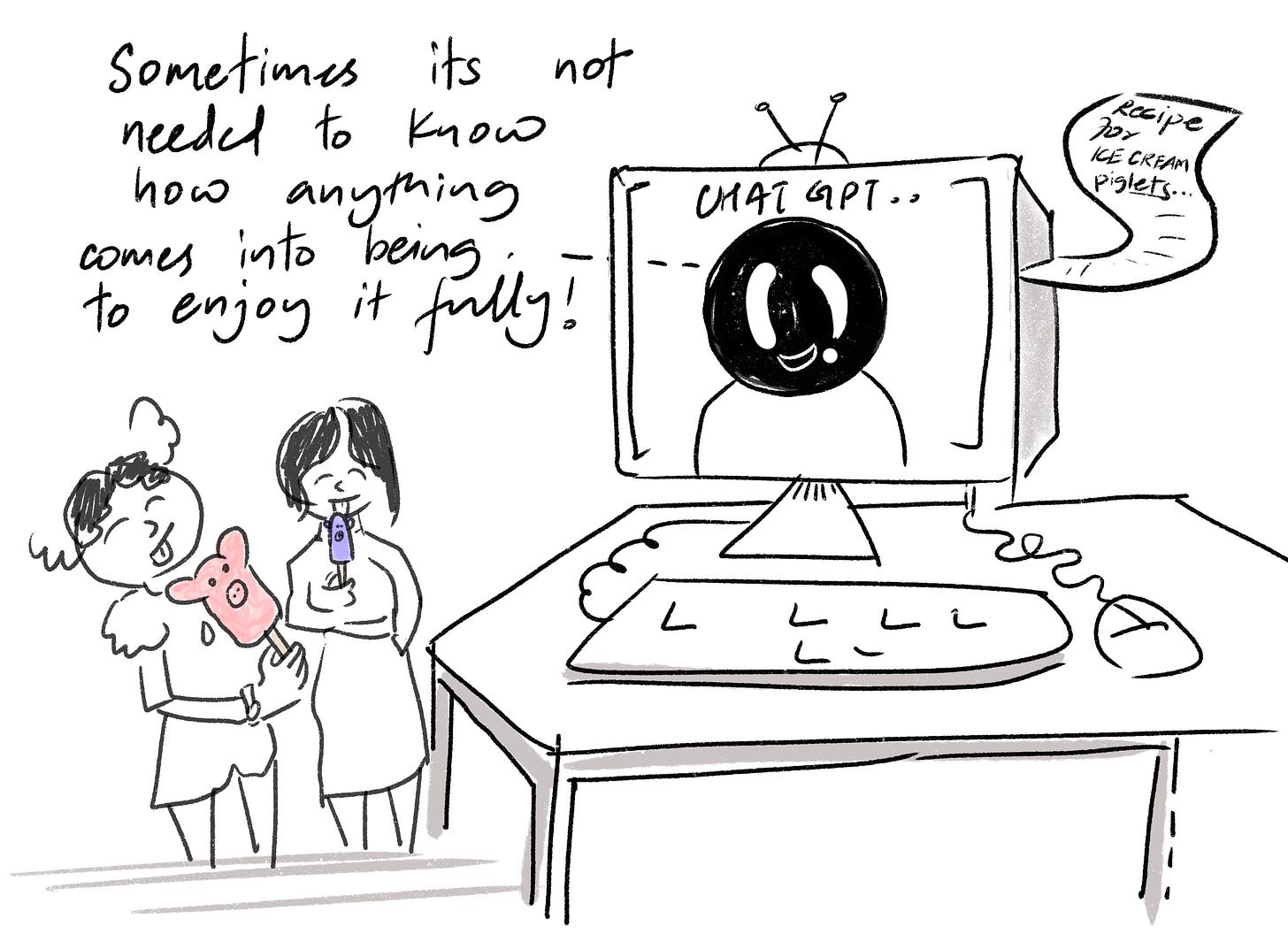

There is something magical about asking ChatGPT to create a presentation or a pitch deck. But AI is far from the only magical technology out there. Chances are, you have flown in an airplane. One moment you’re on the ground and the next moment you’re up in the sky, hurtling towards your destination at nine hundred km/hr. How magical is that? We are used to the magic of flight, and soon enough, we will be used to the magic of AI. Let’s see how to use AI to solve everyday problems that civil society organizations face.

Can we use AI to create better pitches?

For example, Socratus works with content influencers to infuse climate action into their regular (non-climate) content. Can we use ChatGPT to create a good pitch for this work? Let’s see what the machine can do. We fed the following question to ChatGPT:

Behaviour change is one of the hardest problems when it comes to addressing the climate crisis. As we know, young people often take their cues on how to act in the world from social media influencers. So, can you prepare a short report on how we should use social media influencers to create new opportunities for behaviour change in response to the climate crisis?

This is ChatGPT’s response:

To effectively use social media influencers for driving behavior change in response to the climate crisis, here is a strategy that can be considered:

1. Selection of Influencers

Credibility and Alignment: Choose influencers who are genuinely passionate about sustainability and climate issues. Their authenticity is crucial as followers are more likely to trust and emulate influencers who display a consistent and genuine commitment.

Diverse Voices: Include influencers from diverse backgrounds to ensure that the message resonates across different demographics and geographies. This helps in addressing various aspects of climate change that might affect different communities uniquely.

2. Content Strategy

Educational Content: Influencers can share content that educates their audience about the climate crisis, including its causes, effects, and the science behind it. This can be done through infographics, short videos, and interactive posts.

Personal Stories: Sharing personal stories and testimonials about how climate change affects individuals can help in making the issue more relatable and urgent.

Actionable Tips: Provide practical and actionable tips that people can incorporate into their daily lives, such as reducing waste, opting for sustainable products, or methods to reduce carbon footprint.

ChatGPT’s response was much longer, but you get a sense for what it’s wanting us to do. The answer sucks. It’s generic gyan lacking concrete detail. It doesn’t tell you how to differentiate your work from anyone else doing the same thing. Perhaps the fault lies with the questioner and not the oracle? Let’s ask the question somewhat differently:

Can you rewrite this report but with a focus on influencers in India with the kind of challenges that India faces with respect to climate change and of course the immense linguistic, ecological, and economic diversity of India in mind?

ChatGPT’s revised response:

1. Selection of Influencers

Lifestyle Influencers: Focus on influencers who specialize in lifestyle, food, travel, and fashion. These influencers can integrate sustainable practices into their content in a way that feels natural and unforced.

Cultural Diversity: Choose influencers from diverse cultural and regional backgrounds to ensure a wide variety of Indian traditions and practices are represented, which naturally incorporates sustainability.

2. Content Strategy

Embedded Sustainability in Daily Routines: Encourage influencers to showcase daily routines that naturally include eco-friendly practices, such as using cloth bags during shopping vlogs, or featuring biodegradable products in daily skincare routines.

Cultural Heritage and Sustainability: Influencers can highlight traditional practices that are inherently sustainable, like using banana leaves as plates or promoting local festivals that have a low carbon footprint.

Travel Vlogs: Influencers can focus on eco-tourism spots or practices, subtly emphasizing the beauty of preserved environments and the importance of maintaining such locales.

We cut off ChatGPT once again because it was producing hundreds and hundreds of words. Despite the verbiage, this follow-up answer feels more useful than the first one and since we know our work, it might give us clues on the narratives we should be experimenting with. We aren’t sure if this exchange will be useful to someone who hasn’t thought about influencers at all, but the value of AI here is in its speed: instead of having an idea, exploring its usefulness, looking for expert guidance etc (several days worth of effort at the very least), we can ask the AI a series of questions and it will give you enough back to decide whether the idea is worth pursuing.

The Mango Polycrisis

30 minutes instead of 3 days makes for an entirely different economy of exploration; suddenly, we can indulge our whims because it doesn’t cost us much in time (and money). We asked the AI:

What is the impact of the Israel-Palestine conflict on agrarian livelihoods in India?

and a couple of questions later, it zeroed in on the Mango season.

The conflict has led to the suspension of sea exports from India to the region, necessitating a shift to air transportation for mango exports. This has caused a significant increase in air traffic and a consequent 25% rise in airfares, which has made exporting mangoes more expensive. The crisis has made exporting mangoes more challenging, with fluctuating freight rates and difficulty in securing slots. Air freight charges have surged from around Rs 250 per kg last year to between Rs 400 and Rs 550 this year. The increased costs of exporting mangoes due to the conflict are likely to be passed on to domestic consumers. With air freight rates rising, exporters may need to increase the price of mangoes within India to maintain profitability.

As it so turns out, this year is a Mango polycrisis, for the war is only of several crises coming together in a perfect storm:

Bad weather conditions, including extended rain and climate change, have led to late flowering and destruction of flowers, resulting in pest attacks and reduced production . This has contributed to a short supply of mangoes in the Indian market. The severe summer has also triggered higher demand for fruits, including mangoes, which has pushed prices up. The high prices have led to a decrease in demand, with sales limited to 40-50% of the usual, and some stores reporting only 10% of mangoes being sold.

As a brain in a vat, AI won’t teach you that climate change will drive a different agrarian polycrisis every year; this year’s mango problems could be succeeded by next year’s rice problems. What AI does provide - for someone who is attuned to the polycrisis way of thinking - is a quick search for unexpected correlations that would be beyond the capacity of any person, howsoever well informed they might be.

Knowledge as a Commodity

AI is building upon the core function of the internet: search. Google’s mission statement says: “to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Information was scarce in the pre-internet era. You had to go to a library to access reference manuals and encyclopedias. The internet enabled a information society at a very different scale than what came before: the world’s information was suddenly available at your fingertips.

AI is to knowledge that search is to information.

Knowledge has been a scarce resource until now, but that’s about to change, as the world’s knowledge is beginning to be available at our fingertips. It will inevitably lead to the disruption of knowledge work - to use an economic argument, the price of a scarce commodity and what it’s used for is completely different from the price of an abundant commodity and what that can be used for.

Here’s an example. A friend asked a question about an “an 18th century actress who sang bawdy songs with a lute.” Google was useless (search for it!), but ChatGPT gave an answer right away:

Yes, an 18th-century actress known for singing bawdy songs while accompanying herself on the lute was Kitty Clive. Kitty Clive, born Catherine Raftor, was a renowned English actress and singer famous for her comedic roles and musical performances, often including humorous and risqué songs. She was a prominent figure in London's theatre scene during the 18th century.

Now that we have a name, we can research Kitty Clive’s life history on Wikipedia and elsewhere. But that’s not what interested us. The last name, ‘Clive,’ should ring a bell for anyone who knows Indian history, for the person who inaugurated British rule in India was called Robert Clive. Turns out, Kitty Clive was married to a distant relation of Robert, so not much interest there, but this connection piqued our interest about Robert Clive’s family and its current status. Another ten minutes of poking around resulted in this mini-history of Clive’s family:

Note: we had to explicitly ask the AI to take the family’s connection to colonial conquest into account. Otherwise it produced glowingly positive material about the statesmanlike qualities of the Clive family….

The Clive Family: A Critical Historical Overview

The Clive family is famous for its role in British history, but their wealth and power came from the colonization and conquest of India. Their story starts with Robert Clive, also known as Clive of India. Born in 1725, he played a key role in establishing British control in India, a process that involved a lot of exploitation and violence. His victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, which he won through strategic tricks and betrayals, marked the beginning of British dominance in India. This victory allowed the British East India Company to exploit India's resources, making Clive and the company very rich while causing great harm to the local economy and society.

Robert Clive was made Baron Clive of Plassey, a title that celebrated his controversial achievements. He amassed a huge fortune through corrupt practices, which solidified the Clive family's status. His descendants continued to benefit from and perpetuate the systems of colonial rule that he had helped establish.

One notable descendant was his son, Edward Clive, who became the 1st Earl of Powis. Edward was the Governor of Madras from 1798 to 1803, where he continued to enforce British colonial policies, often at the expense of local people. The wealth and power of the Clive family were deeply connected to their roles in the colonial administration and the exploitation of colonized peoples.

The family remained prominent through the 19th and 20th centuries. Robert Windsor-Clive, 1st Earl of Plymouth, born in 1857, was a significant Conservative politician. His education at Eton College and St John's College, Cambridge, prepared him for a privileged life and a career in public service, made possible by his family's colonial wealth.

Windsor-Clive started his political career as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Ludlow in 1878, a position he held until 1885. He then represented the Ludlow division of Shropshire from 1885 to 1904. As Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1900 to 1903, he continued to oversee British colonial policy. His elevation to the peerage in 1905, becoming the 1st Earl of Plymouth and Viscount Windsor, further solidified his status. He served as Lord Lieutenant of Glamorgan from 1890 until his death in 1923. He married Alberta Victoria Sarah Caroline Paget, and they had six children, ensuring the family's continued influence.

Their son, Ivor Windsor-Clive, became the 2nd Earl of Plymouth. Born in 1889, Ivor followed his father's footsteps into politics, holding positions such as Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies and Minister for Works during World War II. His career, like his father's, was supported by the wealth and status from their colonial past.

Ivor married Lady Irene Corona Charteris, and they had three children. His eldest son, Other Windsor-Clive, became the 3rd Earl of Plymouth. Born in 1923, Other served in the Royal Navy during World War II and later in public service, including as Lord Lieutenant of Glamorgan from 1953 to 1957 and West Glamorgan from 1974 to 1988. He also engaged in cultural and charitable activities to maintain the family's public image, despite their wealth's origins in colonial exploitation.

Other Windsor-Clive married Caroline Helen Rice, and they had three children, continuing the family lineage. He passed away in 2018, leaving a legacy of public service and cultural contributions, yet his family's wealth and status remained tied to the dark history of British imperialism and exploitation of colonized peoples.

The Clive family's history, from Robert Clive's conquests to the public service of the Earls of Plymouth, shows how wealth and status built on colonial exploitation can persist across generations, shaping public life while being overshadowed by the injustices of their origins.

The most recent Earl of Plymouth (Other Windsor-Clive) passed away as recently as 2018, so colonial conquest paid off for over two hundred and fifty years. Notice how his name has both Clive and Windsor (the name of the British royal family) in it. Moral of the story: conquest is good for business.

It’s possible ChatGPT is hallucinating some of this information, and if this were an essay about the Clive clan, we would need to verify the AI’s contributions carefully. But that’s not the point of our exercise. We are exploring the possibilities of this technology, not testing its limitations.

What’s the point of all of this?

Conclusion

Once knowledge becomes a commodity, it will be produced in ways that were impossible before. Ten years ago, let alone thirty, if we had to write a book about the connection between imperial conquest and generational wealth, we would have to travel to Kolkata and spend some time in the archives, then travel to England, spend time in the British library, and then take years to write a book that shows how colonialism is still alive. There’s probably a bright historian who is planning on writing such a book right now.

With AI, it might be possible to complete 70% of that historian’s achievement in one afternoon, and that’s enough for most people. It’s a solution for curiosity that doesn’t demand depth. Think about it: how many people would be willing to read an expensive hardcover on Robert Clive’s family and its continuing prominence? Probably not many. But if you could press a button and get a 20,000 word summary of that family, and it came formatted in a nice PDF with pictures and captions, it might be worth an afternoon’s attention.

Human labour is crucial for that 20K word PDF, but it’s a different kind of knowledge work than the historian who spends years researching this topic. It has value, just as Wikipedia is valuable, and like Wikipedia, its value only increases with the network effects of a store of more and more knowledge. Nevertheless, there’s an obvious problem with shallow knowledge, and a world which never demands depth is a dystopia. There will be immense commercial pressure to stay at the surface. Can we design for depth and speed?

Long story short, AI is going to transform knowledge work, and civil society organizations need to be smart about how they create common knowledge resources and new knowledge practices.