Wicked Intelligence 5: Civil Intelligence

Who controls AI?

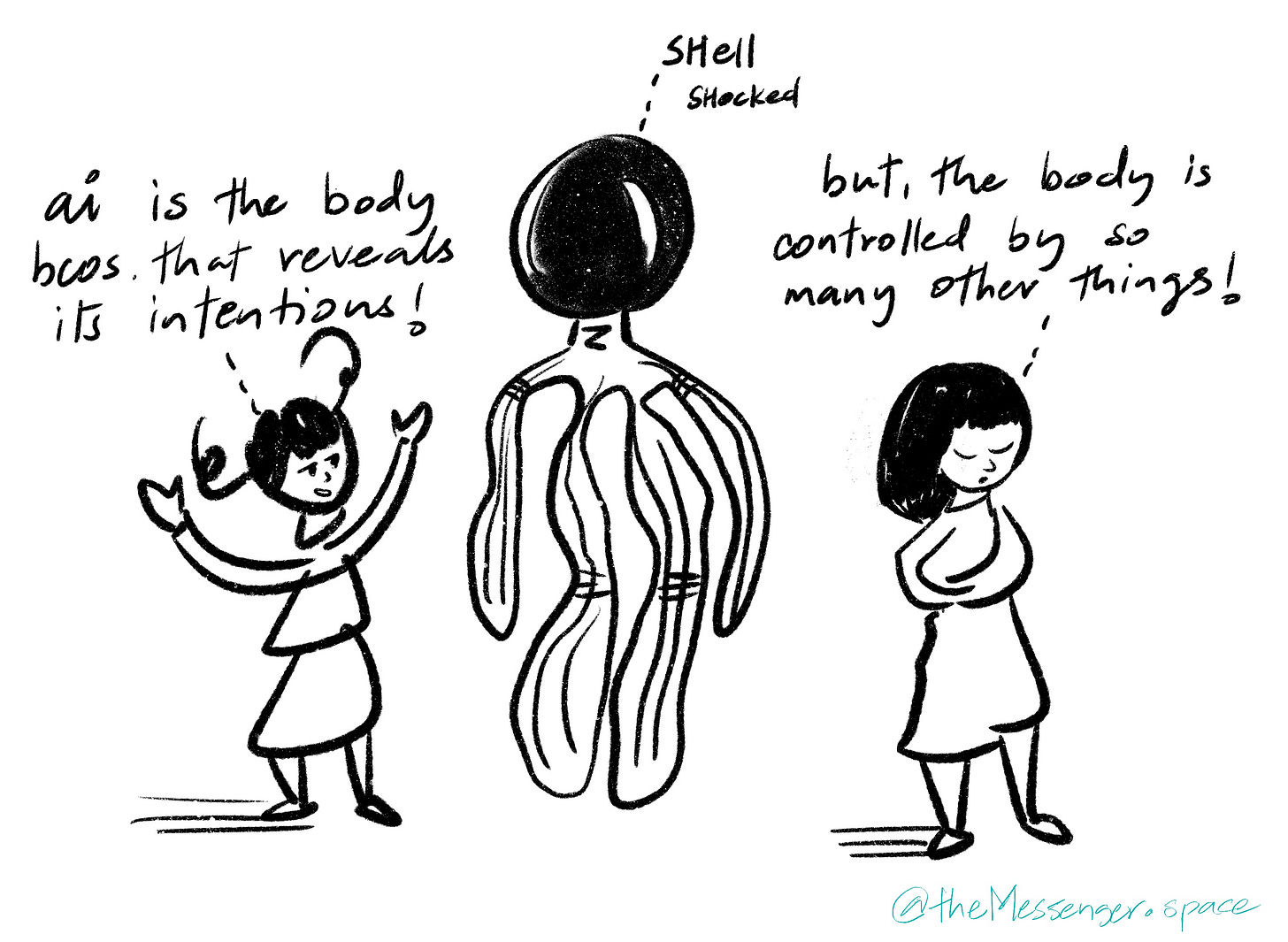

One of our biggest annoyances is when people talk about AI as if it acts on its own. When someone asks if AI will take their job, they know that it's not AI itself doing it. It's actually their boss deciding to automate their job. The decision-making power still lies with humans. If Amazon decides to replace warehouse workers with robots and redesigns the warehouses for robots instead of humans, that's a choice made by Andy Jassy, not some fictional AI like Skynet.

It's important to understand that the way we talk about AI and automation often ignores the real decision-makers. We tend to blame technology for job losses, rather than the people and companies choosing to use this technology. This narrative hides who's really responsible and oversimplifies the complex relationships between technological advancements, economic reasons, and social effects.

When we talk about the future of work and AI, we need to focus on ethical considerations and the possibility for human-centered decisions that aim for fair outcomes. As we move forward with technology, we should aim to use AI to improve human work rather than just replace it, ensuring that technological progress benefits as many people as possible. This means we need to shift our view from seeing AI as an independent force of change to recognizing it as a tool shaped by the values and choices of the people who create and use it.

What values and choices should we bring to the creation and use of AI?

Should we prioritize maximizing profit and efficiency, even if it means displacing workers and widening economic inequalities? Or should we aim for a more equitable distribution of the benefits of AI, ensuring that everyone has a chance to thrive in a changing economy? Should we focus on developing AI systems that augment human capabilities and create new opportunities for meaningful work, or should we accept the inevitability of job displacement and focus on providing a social safety net for those affected?

These questions raise deeper ethical considerations about the very nature of work and its role in society. Should work be primarily a means to an end, a way to earn a living and secure basic necessities? Or should it also provide a sense of purpose, meaning, and fulfillment? If AI can automate many of the tasks that humans currently perform, what will that mean for our sense of identity and self-worth? How will we find meaning and purpose in a world where machines can do so much more than we can?

Furthermore, as AI systems become increasingly sophisticated and autonomous, we must grapple with the question of responsibility and accountability. Who is responsible when an AI system makes a decision that harms or discriminates against individuals or groups? How do we ensure that AI systems are transparent and explainable, so that we can understand the reasoning behind their decisions?

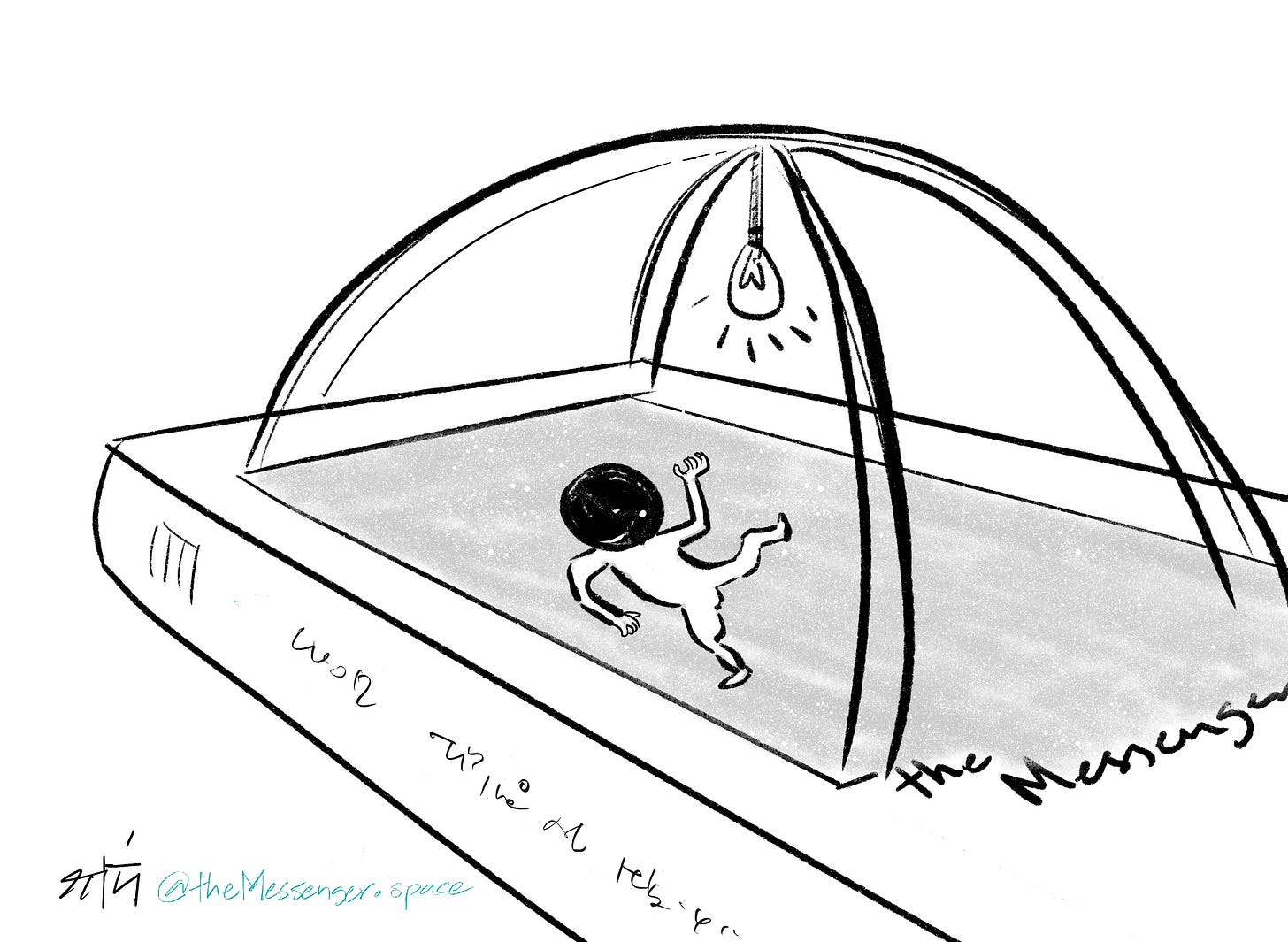

Ultimately, the values and choices we bring to the creation and use of AI will shape the kind of future we create. Will it be a future where technology serves humanity, or one where humanity becomes subservient to technology (or more likely, subservient to the owners of technology)? The answer lies not in the hands of AI itself, but in our own. Right now, AI is going through a phase of chaotic development dominated by a few, very well funded, companies. There might be national efforts under way as well, in countries such as China and India. There are questions about the ownership of the data used to train the models, with some pushing for open-sourcing both the training data as well as the algorithms. These are important questions, but we won't engage with them here. Instead, we want to ask:

How should civil society engage with AI?

AI and Civil Society

Of the three big chunks of modern life - State, Market and Society - society is far behind the other two when it comes to AI. Market players are dominant, with your likelihood of getting funding (and maybe users as well) much higher if you say ‘I sell AI powered fruit juice’ instead of plain fruit juice. State based efforts are also well funded, often for national security reasons, though it's not clear if they can afford the talent needed to create cutting edge AI. Civil Society has neither the money nor the prestige to compete with the other two. Is it consigned to irrelevance?

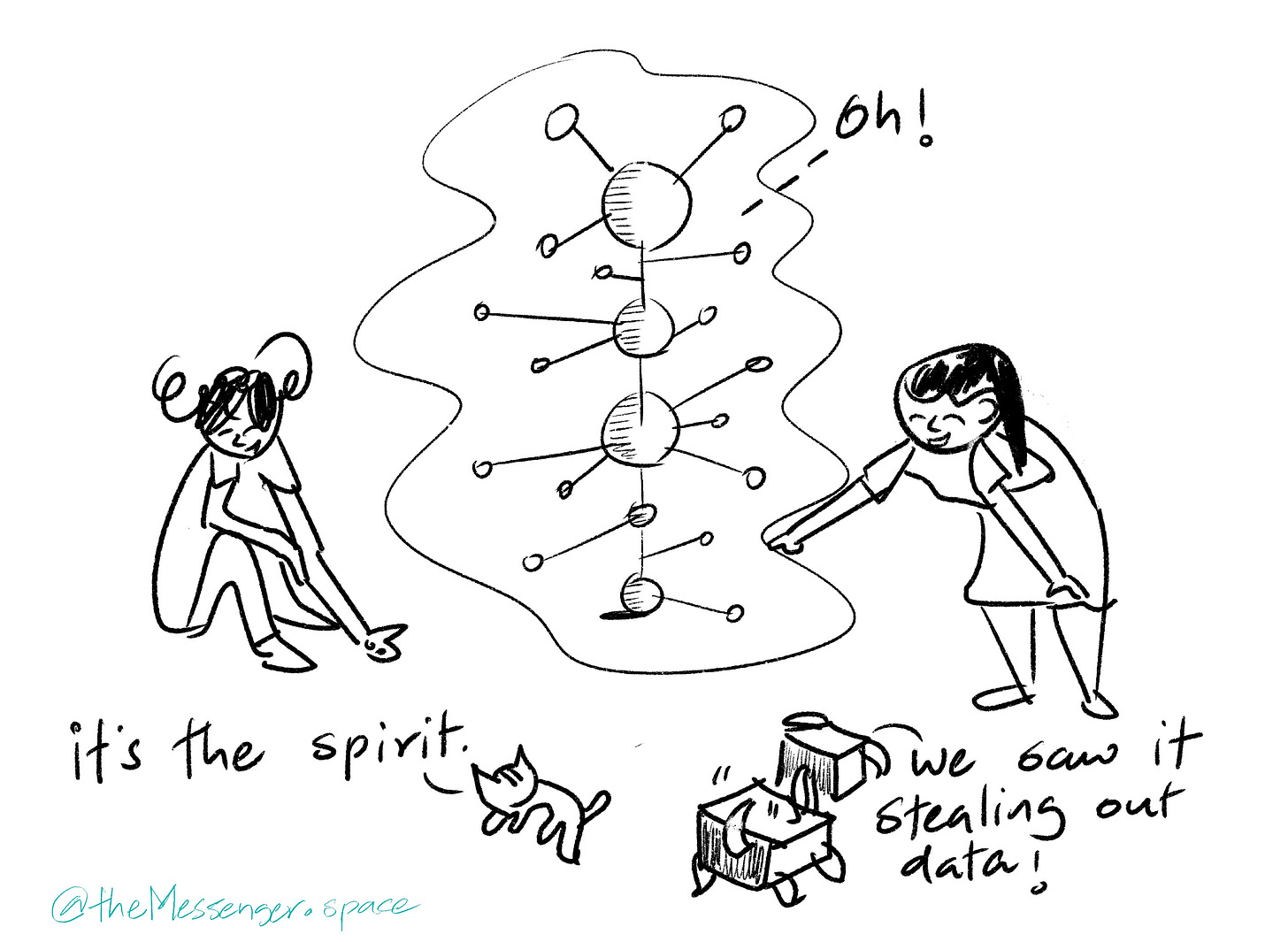

As of today, the answer seems to be an unfortunate 'yes.' What's the big deal though? It's not as if civil society has any role in the making of cars or potato chips. Why should AI be any different? Our answer: perhaps we should experiment with cooperatively manufactured cars (and definitely potato chips), but whether we do so or not, AI is different. AI mechanizes the production and reproduction of knowledge, and in the modern era, we have mostly agreed that knowledge should be universal and available in the public domain for anyone to repurpose. Traditional knowledge producing/reproducing institutions such as universities and schools are often public institutions. However, the emergence of AI threatens to disrupt this delicate balance. If AI becomes solely the domain of private corporations and state actors, the democratization of knowledge could be reversed. The algorithms that shape our understanding of the world and guide our decisions could become proprietary and inaccessible to the public. The potential for bias and discrimination inherent in AI systems could go unchecked and unchallenged.

Civil society has a crucial role to play in ensuring that AI serves the public good. It can act as a watchdog, scrutinizing the development and deployment of AI systems to ensure they are transparent, accountable, and fair. It can advocate for open-source models and data, ensuring that the knowledge produced by AI is accessible to all. It can raise awareness of the potential risks and harms of AI, and push for regulations that protect individuals and communities from discrimination and exploitation.

While civil society may lack the financial resources and political clout of the market and the state, it possesses something far more valuable: the trust and legitimacy of the people. By harnessing this power, civil society can ensure that AI is developed and used in a way that serves the interests of all, not just the privileged few.

Left to its current devices, AI will accelerate the corporatization of knowledge while training its models on the knowledge shared by the very public it will replace with machines. That's not good is it? Fortunately, there's an opportunity for civil society to make an essential contribution: no technological development is only about its artifacts alone, but also about the human social institutions that emerge along with the artifacts. Steam engines were a new technology 250 years ago, but in order to produce textiles in factories powered by steam, you needed new machines, but also new ways of organizing labour.

Wystem 4: EPIs

Don’t have too much time? Watch the video👇🏾 and read the summary. Summary We live in a world deeply intertwined with the written word, where ancient inscriptions like those on Ashoka's Pillars not only convey historical narratives but also showcase exquisite artistry, blending visual art with textual communication. The Sanskrit term "lipi," which denot…

If data is the new oil and AI the new machines that take advantage of this information source, then what are the new social formations that take advantage of data and AI to promote flourishing? Our answer - not the only right answer but one we are fond of - is: ecosystems. As we have written before, one practical approach to building trustworthy ecosystems is through the concept of relays, akin to those in a relay race, where the baton (information) is passed seamlessly between organizations.

Ecosystems for Civil Intelligence

The question then becomes: how do we design and cultivate these ecosystems? We must move beyond the traditional, hierarchical structures that have dominated our institutions for centuries and embrace a more decentralized, networked approach. This means empowering individuals and communities to take ownership of their data and participate in the development and governance of AI systems. It means fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing across disciplinary boundaries, creating spaces where diverse perspectives can converge and generate new ideas.

The closest commercial analogue to what we are imagining is in the latest announcement by Apple (what they predictably call ‘Apple Intelligence,’ or AI, get it?). Apple has a huge user base and owns the operating system that can grant selective access to AI applications. Some of the core AI functions are going to be delivered by Apple itself (such as a much better Siri), but they have announced a partnership with OpenAI to use ChatGPT for more complicated use cases. This is what Stratechery has to say about Apple’s announcement:

To put it another way, and in Stratechery terms, Apple is positioning itself as an AI Aggregator: the company owns users and, by extension, generative AI demand by virtue of owning its platforms, and it is deepening its moat through Apple Intelligence, which only Apple can do; that demand is then being brought to bear on suppliers who probably have to eat the costs of getting privileged access to Apple’s userbase.

Apple is using its market power to insert itself as an intermediary between AI companies and users. Can we learn from that model? What would a ’public intermediary’ for AI look like, one that mediates the relationship between CSOs (and even for-profits) and citizens?

Any intermediary should be grounded in a deep understanding of the local context and needs of the communities they serve. They should be designed to empower individuals and communities to solve their own problems, rather than imposing top-down solutions. This requires a shift in mindset from seeing AI as a tool for control and optimization to one that enables agency and autonomy. The concept of relays (and the EPI), as mentioned earlier, offers a powerful metaphor for this networked approach. Information flows through the ecosystem, not as a commodity to be hoarded or exploited, but as a shared resource that enables collective learning and action. Each organization, each individual, plays a role in this relay, adding value and contributing to the overall flourishing of the community.

Whether we do with technology or via old fashioned human to human connection, any system that makes it possible for information to be relayed fluidly at scale is an AI system. Even better: by learning to create and work in organizations that can collaboratively foster flourishing communities, we will learn to be the kind of human being who is most capable of taking advantage of AI. It doesn't matter whether the ecosystem uses AI as a technology as long as it borrows from the language of fluid intelligence.

AI is already being built on top of our collective wisdom (and collective biases, unfortunately). What if we consciously chose to take control of that training? Can civil society take the lead in new forms of collective wisdom?

By participating in these ecosystems, we not only create a more equitable and sustainable future for AI, but we also transform ourselves. We become more collaborative, empathetic, and adaptable. We learn to navigate complexity and uncertainty, to embrace diversity and difference. In short, we become the kind of human beings who can thrive in a world where AI is not just a tool, but a partner in our collective journey towards a better future.

We have spent the last ten weeks on exploring the artificial - first with the Wystem and then with AI. Starting next week, we will switch focus to the natural world and talk about Socratus’ initial forays in multispecies existence.