Thinking in Public: The Gender Polyconflict, Part 5

Over the past few weeks, we've shared a four-part series examining gender and development in India through a new lens we call "polyconflict." This last essay in this series is a synthesis of our key findings along with lessons for anyone working on gender equality, development, or policy in India and beyond. Nothing we have said is news to experts, but our hope is that we have put together a package of ideas, data and code (link to Github) of use to anyone interested.

Why We Moved from Polycrisis to Polyconflict

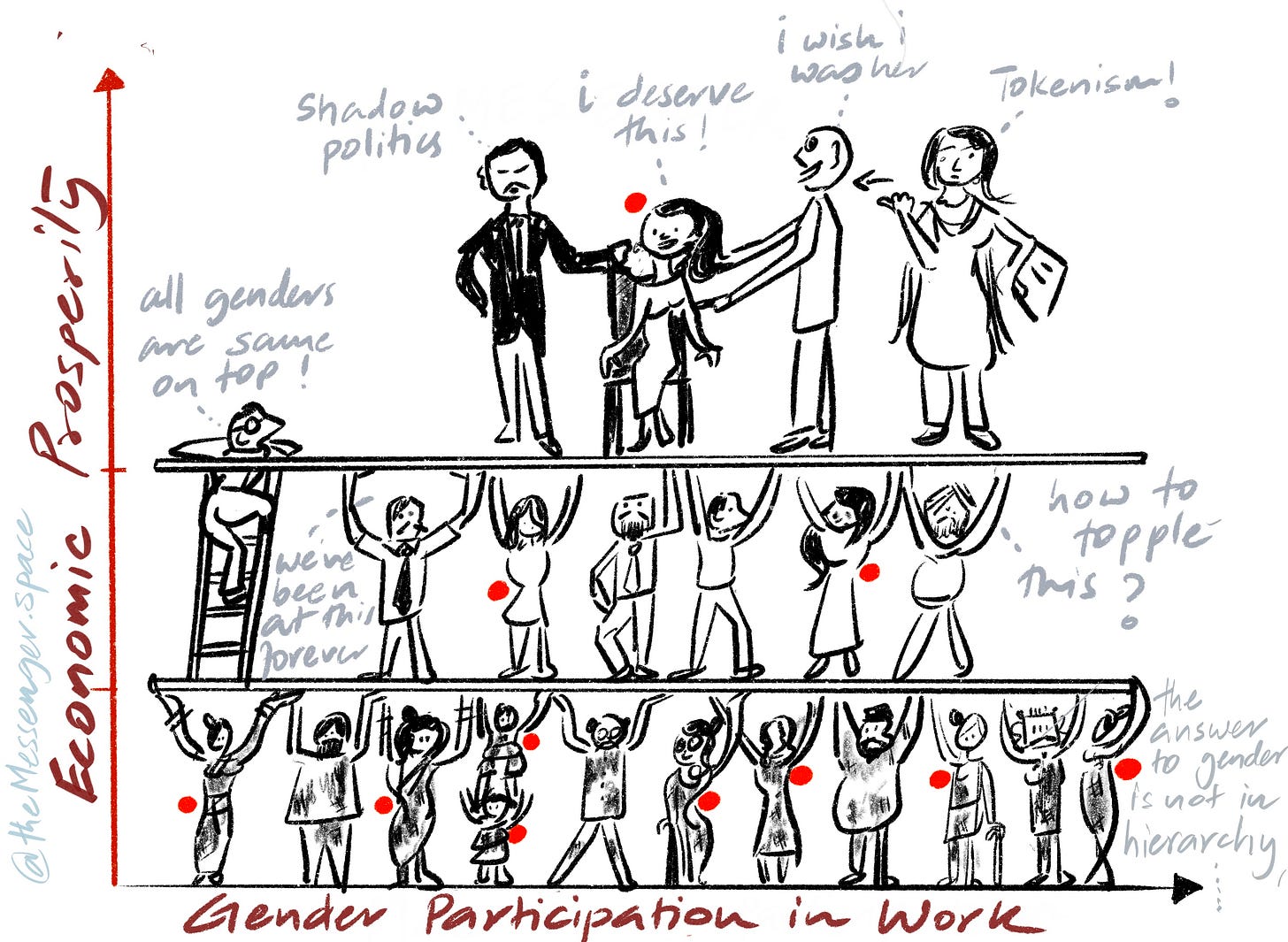

We began this series frustrated with how the term "polycrisis" - popularized after 2020 to describe converging global risks - still treats our challenges as temporary disruptions that clever management can fix. Through our analysis, we realized these aren't crises waiting to be solved. They're permanent struggles over power, resources, and meaning that will define our societies for generations.

This shift in thinking matters. When we see gender inequality as a crisis, we look for quick fixes and technical solutions. When we recognize it as polyconflict - an enduring struggle that mutates rather than ends - we prepare for the long work of navigation rather than the false hope of resolution.

What We Discovered About Gender as the "Third Rail"

In our analysis, we identified gender as the "third rail" of polyconflicts - while climate sets our physical boundaries and technology determines what's technically possible, gender influences who gets to be a legitimate author and beneficiary of our future. Drawing on Patricia Hill Collins's Matrix of Domination, we mapped how gender inequality in India operates across four interconnected domains:

Structural: Women face systematic barriers through law and policy, from political under-representation to missing infrastructure like childcare and safe transport

Disciplinary: Institutions undermine gender equity despite formal policies - think of unequal pay for female athletes or police failure to address violence against women

Hegemonic: Culture and media circulate oppressive ideas, from Bollywood stereotypes to marriage customs treating women as property

Interpersonal: Individual choices reinforce inequality, like assuming women will handle all domestic labor while maintaining careers

These domains don't just coexist - they reinforce each other in ways that make inequality feel natural and permanent.

The Economic Freedom Paradox We Uncovered

We chose to focus on women's workforce participation because economic freedom is foundational to human dignity and autonomy. What we found challenged many assumptions.

The data revealed a striking paradox: India has achieved remarkable progress in women's education and dramatic fertility declines - both traditionally associated with gender equality - yet women's workforce participation has actually fallen. From 35% in 2005 to just 19% in 2021 (now recovered slightly to 31.24% in 2023), India sits in the bottom 10% of countries globally.

This decline cuts across all demographics - rich and poor, urban and rural, all castes and religions. Even more puzzling, it happened during a period of rapid economic growth.

Gender and a potential Constitutional Crisis

Our analysis revealed how India's gender polyconflict could spark a constitutional crisis. Southern states that invested in women's education and achieved European-level fertility rates (1.6-1.8 births per woman) now face losing parliamentary seats to northern states with higher fertility (2.3-3.0) when delimitation happens after 2026. Tamil Nadu's Chief Minister has already called this "penalizing success." We see this as a perfect example of polyconflict - where progress in one domain (fertility reduction) creates new struggles in another (political representation).

Data Challenges

One of our most frustrating discoveries was the state of gender data in India. We described our search for comprehensive state-level gender data as "much more of a nightmare than a dream." The most recent census is from 2011 - 14 years old! This data gap severely hampers evidence-based policymaking and meaningful accountability measures.

When we did analyze available data, we found surprising patterns that challenge conventional wisdom. Rural SC/ST populations often showed better gender equity in workforce participation than urban upper-caste groups. Urban general caste populations had 403 male workers per 100 female workers, while rural SC/ST populations had only 150. This suggests that necessity, not progressiveness, might drive more equitable participation in disadvantaged groups.

Our Case-Making Methodology

Traditional research takes 3-5 years from study to policy implementation - far too slow for rapidly evolving polyconflicts. We developed a "case-making" approach that creates structured arguments coupling evidence with actionable proposals. Cases must be:

Contextual (tailored to different stakeholders)

Actionable (implementable in weeks, not years)

Adaptive (able to incorporate new data)

Robust (surviving handoffs between researchers and policymakers)

We demonstrated this by building our case around women's workforce participation, showing how state investment succeeded in family planning and education but lack of state investment has led to failures in women's economic participation.

What Tamil Nadu Taught Us

Our deep dive into Tamil Nadu revealed how gender polyconflicts operate at every scale. Even within this relatively progressive state, we found enormous variations. Some districts compare with much richer nations in human development, while others score lower than Bihar.

Chennai exemplified a key pattern: near-equal population sex ratios mask huge workforce disparities, suggesting that economic development can actually increase gender inequality as families choose to keep women at home.

Why This Matters Now

Recent developments confirm the urgency of our analysis. The Constitution (106th Amendment) Act, 2023, has also reserved one-third of all seats for women in Lok Sabha and state legislative assemblies, potentially addressing some structural barriers. Yet India ranks 120 among 131 countries in female labor force participation rates and rates of gender-based violence remain unacceptably high.

Besides the justice concerns, the economic implications are staggering. Achieving gender equality could add hundreds of billion of dollars to India's GDP, but this won't happen through economic policies alone - it requires confronting the entire matrix of domination simultaneously.

Our Key Takeaways

Through this series, we've learned that:

Gender conflicts are permanent features, not temporary problems - The polyconflict lens helps us prepare for long-term navigation rather than quick fixes.

Progress is uneven and contradictory - Success in education and fertility coexists with failure in economic participation, showing how patriarchal structures adapt to maintain control.

Data gaps are a major challenge - The 14-year census gap represents millions of women whose struggles remain uncounted and unaddressed.

Scale matters - National averages hide regional variations, while regional successes mask local inequalities.

State commitment works, when it exists - India's success in education and family planning shows change is possible, but requires sustained state investment.

This is the End

We end where we began, with our modification of Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous quote: "There are many arcs, and they bend towards justice at different rates." India's gender polyconflict shows these arcs - in education, fertility, political representation, and economic participation - moving in contradictory directions.

Understanding these contradictions, measuring them accurately, and developing adaptive strategies to navigate them is the work not of a moment but of generations. The polyconflict lens helps us see this work clearly - without false optimism or paralyzing despair - as the long struggle it has always been.

We hope this framework proves useful in your own work. Whether you're in policy, activism, research, or development, recognizing gender struggles as enduring polyconflicts rather than solvable crises can help us all engage more effectively with the deep structures that shape our societies.

Our code to compute the statistics and create the data visualisations in this series is available here on GitHub.