Thinking in Public: the Case for Gender, Part 2

Seeing the Gender Polyconfict in the everyday

In Part 1, we proposed shifting from the Polycrisis paradigm—which attributes systemic shocks to economic, ecological and social factors—to Polyconflict, which better captures the world's landscape of enduring struggles. Polyconflict, on the other hand, represents the state of the world at any instant as a metamorphosis of prior conflicts and the actions undertaken to navigate them – the everyday struggles of individuals and institutions.

Consider India's looming delimitation conflict. The economically prosperous Southern and Western states face potential loss of political representation to the more populous North. While successive governments have delayed this redistricting through constitutional amendments, the eventual redrawing of constituency boundaries could transform this simmering tension into open conflict. The North may demand increased representation based on population, while the South—feeling punished for its development success—might resist to the point of constitutional crisis. This conflict exemplifies how seemingly technical governance issues mask deeper power struggles.

We argued last week that the delimitation polyconflict is gendered and so is every other one; whether it is climate change deepening existing gender gaps, or technology failing to serve female bodies and even enabling brazen misogyny. To give just one example:

Climate change will exacerbate migration.

Migration is typically gendered since men migrate for economic reasons in larger numbers. There’s a twist in the tale though - the way migration data is collected in India (crossing district boundaries), the largest group of migrants in India, by far, are women who move to their husband’s household after marriage.

Economic migration cause by climate distress will lead to more households headed by women, which in turn

Leads to shifts in household power dynamics and potential conflict between traditional gender roles and economic necessities.

Analysing the Gender Dimension of Polyconflicts

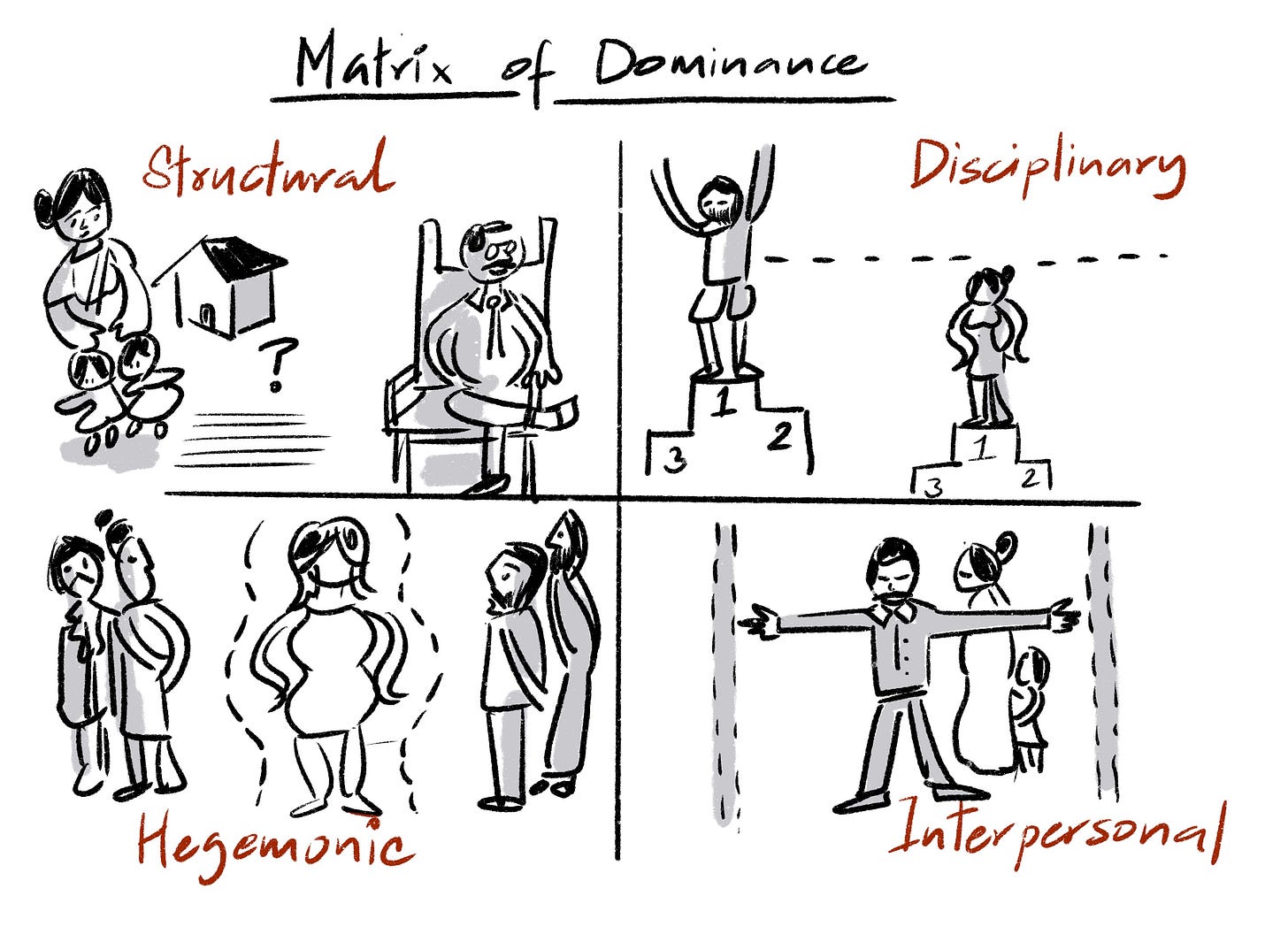

In Part 1, we identified gender as the "third rail" of polyconflicts—a fundamental force shaping how societies navigate change. While systems of power perpetuating gender divides take new forms, they remain deeply entrenched and interconnected. As three men born into caste privilege, we acknowledge our position while drawing upon feminist scholarship to analyze the gender dimension of polyconflicts. In their 2023 book titled “Data Feminism”, scholars D'Ignazio and Klein shine light upon sociologist Patricia Hill Collins’s matrix of domination, first published in 1990 in her book Black Feminist Thought. The matrix has four domains - Structural, Disciplinary, Hegemonic and Interpersonal.

The structural domain encompasses systemic factors perpetuating gender inequity through law and policy. In India, this manifests in three critical ways:

Persistent under-representation of women in state and national legislatures

Insufficient infrastructure and social goods essential for women's participation—from public transport and water access to childcare facilities and sanitation

Discriminatory laws that deny equality to gender minorities.

The disciplinary domain reveals how institutions systematically undermine gender equity despite formal policies promoting it. While India has comprehensive anti-discrimination laws, their enforcement reflects deeper biases:

The state's unequal treatment of male and female athletes in national sports, exemplified by cricket team pay disparities, normalizes gender-based value judgments

Educational institutions reinforce occupational segregation by concentrating women in teaching roles, limiting their presence in administration and leadership

Law enforcement's persistent failure to address violence against women exposes how institutional practices preserve rather than challenge gender hierarchies.

These patterns show how formal equality often masks sustained discrimination through institutional practice.

The hegemonic domain comprises factors that circulate oppressive ideas in culture and media. Film has long cornered the imagination of the public in stereotypes: effeminate men in villainous and comic roles, women bodies offering entertainment to men in item numbers and clothing that make it uncomfortable for women to take on physically challenging roles. Cultural institutions like marriage have long enshrined forms of kanyadaan, the handing over of brides to the groom’s families, as if they were objects. Tokenism in various institutions of installing women (perhaps, particularly, the intersectional caste-disadvantaged women) in nominal positions of leadership are commonplace. While media reports of token installations may be seen as offering inspiration to the tokenised communities, it more often serves to signal institutional equity – masking, rather than addressing, underlying inequities.

Individual choices that undermine gender equity fall within the interpersonal domain. As monumental as structural, disciplinary and hegemonic factors are, everyday actions made within institutions such as marriage and home often further reinforce factors in the other domains. The notion that the woman does the cooking and the cleaning, the school runs, care for the elderly, and where applicable, also formal employment all but presupposes superhuman ability in women, though without any of the glory.

This invisible labour that supports economies and families alike, is not accounted for in economic statistics. It is easy to see that these structures and factors convulse beyond inter-domain borders. As awareness of these power dynamics grows, it inevitably intensifies conflicts for freedoms, resources and acknowledgement, creating opportunities for transformative economic but also leading to broader polyconflicts.

Building our Case: Zeroing in on Economic Freedom

Among the many intersecting struggles, the conflict for economic freedom holds unique potential to disrupt and reconfigure the entire matrix of domination. Economic freedom is foundational to human dignity, autonomy, and the capacity to refuse domination. Without it, women cannot independently control the conditions of their survival and can, therefore, be forced into dependency, submission, or silence. We therefore focus the remainder of this essay on one aspect of women’s economic freedom: their participation in the workforce.

We sourced data from the World Bank to contextualise the Indian predicament on the world stage. The world over, it is much more of a norm rather than not, that GDP per capita is correlated with female participation in the workforce. Even among SAARC countries, India, Sri Lanka and Myanmar are the only off-norm countries, with Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh having near perfect (≈ +1) correlation between the two metrics. In this context, positive correlation means that GDP per capita and female labour force participation move in the same direction; if one increases, so will the other, and vice versa. Negative correlation means the opposite. Correlations are scaled to have values between -1 and 1, where the extreme values (-1 and 1) indicate exactly proportionate movements in the two metrics.

As you can see, the interaction between per capita GDP and labour force participation isn’t straightforward. China is a suprising outlier, for example. We will continue this data driven analysis in the next essay in this series.

If we zoom into the India story, barring the pandemic year of 2020, India has seen steady growth in GDP per capita, but a steep decline in female participation in the workforce since 2005 and barely a recovery back to the 1990s level, even as late as 2023. At 31.24% in 2023, India’s female workforce participation rate sits with the lowest 10% of the countries in the world.

(Source: The World Bank, accessed on May 4, 2025)

As we saw in the previous section, the intersection between gender and other social factors is complex. On the one hand, we see ongoing drops in fertility rates across the country, and historically, that’s correlated with more gender equality. We also see greater numbers of women getting educated, which is also correlated with more gender equality, but then we also see that workforce participation for women is decreasing in the very same period. One key difference between the fertility and education achievements and the decline in workforce participation is the role of the state.

Family planning has been a priority of the state ever since independence and has had its own ministry - the Ministry of Family Welfare - for a long time. Similarly, the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan has worked hard at achieving universal literacy across India, both for women and for men. Unfortunately, we haven’t seen anything like those two efforts when it comes to female workforce participation. Critical investments in childcare, safety, and transportation infrastructure remain severely inadequate. The success stories of education and family planning demonstrate a crucial lesson: transformative social change requires sustained state commitment through policy frameworks, financial investment, and institutional support.

Concluding Words

The gender polyconflict is not a discrete problem to be solved but a multidimensional struggle embedded within the very fabric of economic, cultural, and institutional life. From the invisibilised labour of women in the household to the absent infrastructure that prevents their economic participation, every domain - structural, disciplinary, hegemonic, and interpersonal - is shot through with gendered asymmetries. And while progress in education and fertility reduction show that change is possible when the state commits itself, the absence of a parallel investment in women's economic freedom reveals the limits of partial reform.

As we saw in Part 1, these conflicts manifest differently across contexts - from electoral divides in developed democracies to demographic tensions in India. The role of good data (or sadly, the lack of it) becomes crucial in devising appropriate economic policies to address these complex manifestations. In the next essay, we will leverage available data, particularly the 2011 census, to examine the intersection of economy and gender in India more deeply. The fourth essay will then narrow our focus to one state, analyzing how these dynamics play out at local levels and demonstrating how the gender polyconflict operates across multiple scales of social organization.