Solving in Public II: The Architecture of Heat Action Plans

Everyone and their grandmother knows that software design must be user centric, that if it doesn’t help the user get their job done, it’s a failure. On the flip side, good app designers have a user persona in their design brief, and they design with that user’s needs in mind. Which is why WhatsApp and Telegram and Signal have different solutions to the same problem.

Why shouldn’t governments - and public problem solvers more generally - act like designers? Why shouldn’t they package the same information in different ways for different audiences? Seems like the natural thing to do isn’t it? We suppose that’s what design thinking was meant to do for government (an obvious client), and many a design thinking workshop has been offered for IAS officers or health department doctors and so on.

Design thinking has its critics. A lot of the criticisms have to do with the snake oil version of the method, which promises dramatic results but is actually designed to pad the bottom line of the consultant. We can set those aside. At a deeper level, many uses of design thinking in public founder on the difference between a user and a citizen. To give one important difference: when things fail, a user can complain and perhaps they will be heard, but ultimately, they don’t have recourse. All they can do is move to a different product. But a citizen must always have recourse. Another difference: citizens can’t be treated as customers and the quality of the service shouldn’t depend on how much money they can put on the table. There’s no Business Class citizenship that’s different from Economy Class citizenship. In another context, we read:

But today, consumption and monetization have become strangely mixed up with the idea of good citizenship (a concept that now includes corporations). In fact, the word consumer has become more or less a synonym for citizen, and that doesn’t really seem to bother anyone. “Citizen” implies engagement, contribution, give- and- take. “Consumer” suggests only taking, as if our sole role is to devour everything in sight, in the manner of locusts descending on a field of grain. (from page 12 of Marcia Bjornerud’s lovely book on Timefulness.)

Let’s not be locusts. But what about the hapless citizen? You might argue that of course there are different categories of citizens! Of course some are more equal than others. Maybe so, but can design be an instrument for equality and dignity, and when choices and trade-offs (inevitable) have to be made, can we do always make them in favour of the neediest? Our romantic hope is that ‘design for the public’ is political, but if done well, it can be an innocuous way to insert ideas of justice into the public domain.

We want to distinguish tradeoffs from their consumerist cousin, the cost-benefit. As the previous quote says, citizens have to give and take, i.e., make trade-offs, but costs and benefits are problematic, especially when the costs are to the needy and the benefits to the powerful.

Flowcharting the Heat Action Plan

The Delhi Heat Action Plan is a comprehensive guide for managing heat waves in (where else?) Delhi. It outlines the various health risks posed by extreme heat, identifies vulnerable populations, and details a multi-phase strategy for preparedness and response. The plan includes measures for early warning systems, capacity building for healthcare professionals, public awareness campaigns, and mitigation efforts such as cool roof deployment, increased green cover, and improved access to drinking water. The plan also addresses the need for inter-agency coordination and highlights the importance of leveraging traditional knowledge and cultural practices in heat wave management. Looking at the plan, we can identify a rough timeline and some of the key players:

Timeline:

The phases of the Delhi Heat Action Plan 2024-25:

Phase 1: Pre-Heat Season (January-March)

Phase 2: During Heat Season (April-July)

Phase 3: Post-Heat Season (July-September)

Key Players:

The following agencies are identified as key players in the Delhi Heat Action Plan 2024-25:

Delhi Disaster Management Authority (DDMA): The lead agency responsible for coordinating and implementing the Heat Action Plan.

India Meteorological Department (IMD): Provides weather forecasts and heat wave warnings, triggering the plan's phases.

Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD): Manages cooling centers, water availability, shade, and public health services.

Health Department: Responsible for medical preparedness, training, public health advisories, and reviewing heat-related illnesses.

Labour and Employment Department: Protects workers from heat stress and enforces workplace safety measures.

Information and Public Relation (I & PR) Department: Raises public awareness about heat waves and the action plan.

Other Key Agencies: Delhi Jal Board, Delhi Fire Services, Delhi Police, Transport Department, Education Department, Animal Husbandry Department, NGOs, and community groups.

General Public: Encouraged to stay informed, follow health advisories, and assist vulnerable individuals.

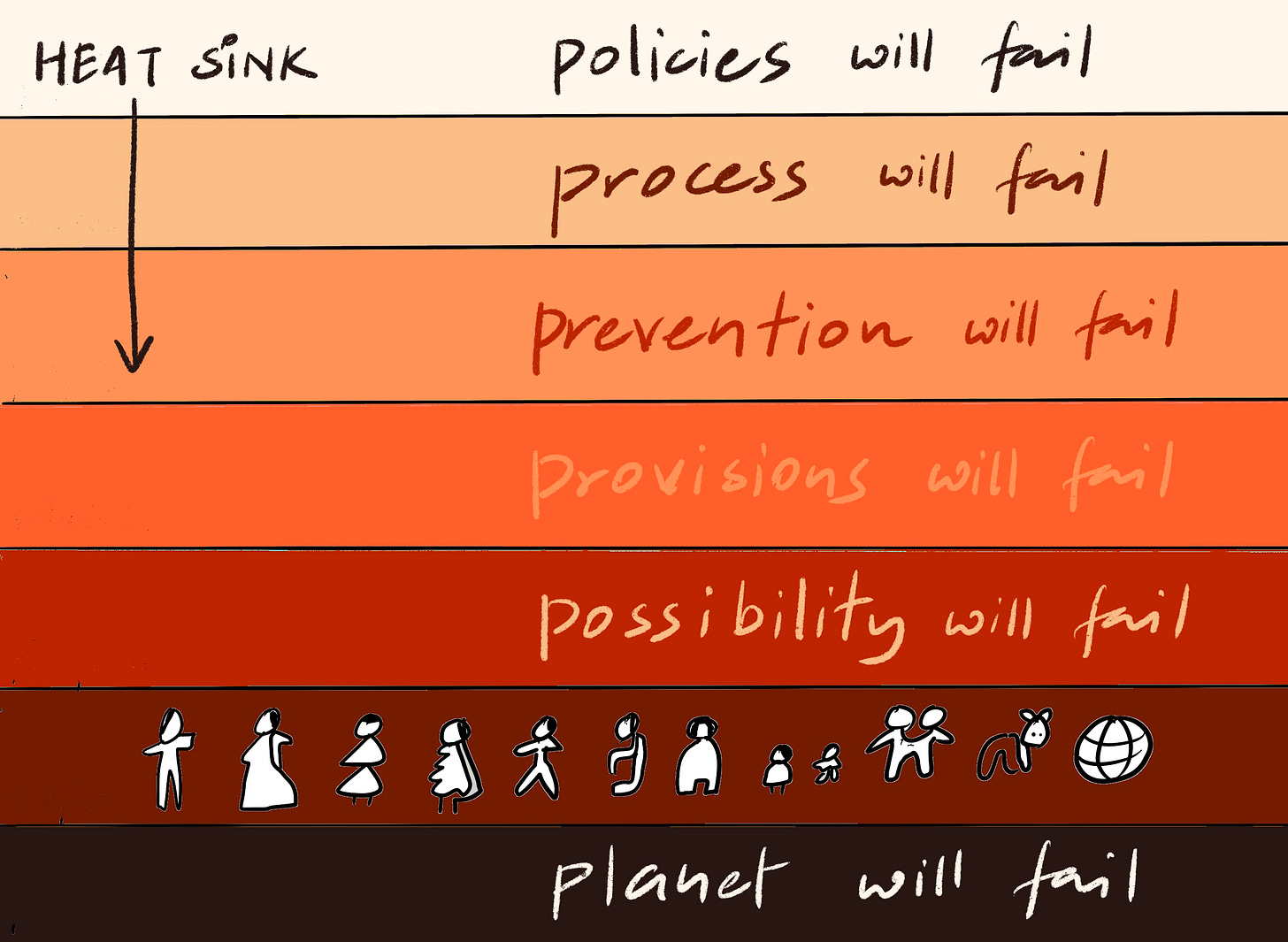

If you go back a few weeks to our idea of an Ecological Programming Interface (EPI) 👆🏾, you can imagine that an EPI will be eminently useful for a heat action plan. For example, you want information (and control) to flow programmatically from the IMD to the labour department and from there to the health department and from the health department to the general public. Once you think in this programmatic, way you immediately see gaps to be filled. For example, where are the various employers whose employees are the concern of the labour department. Why are they not involved programmatically, so that they can provide services complementary to (or in addition to) those provided by the government? That programmatic approach can be brought to the plan as a whole:

Phased Approach: The plan outlines a three-phase approach: Pre-Heat Season (January-March), During Heat Season (April-July), and Post-Heat Season (July-September). This allows agencies to focus on specific tasks and priorities within each timeframe. For instance, the MCD might prioritize inspecting and preparing cooling centers during the pre-heat season, while the Health Department focuses on training healthcare professionals during that same period. Can they coordinate, perhaps even war game their response to extreme heat days?

Trigger Points: The IMD's weather forecasts and heat wave warnings act as triggers for activating different phases of the plan and escalating responses. Agencies would need to be prepared to respond promptly when the IMD issues alerts, initiating pre-determined actions according to their roles. Can these trigger points and subsequent activation flow to non-governmental stakeholders such as employers?

Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation: The Post-Heat Season phase emphasizes evaluating the plan's effectiveness and revising it based on lessons learned. This suggests that agencies would need to track their performance, collect data, and participate in review meetings to identify areas for improvement. How transparent can we make these monitoring exercises?

The plan also highlight specific agencies whose responsibilities are to protect others from heat-related risks. For example:

The Labour and Employment Department is tasked with protecting workers from heat stress.

The MCD and other agencies are responsible for providing shade at public places and construction sites, which impacts the public at large. Is this an opportunity for public problem solving? See this competition to design cheap shades!

The plan emphasizes individual preparedness and community engagement in mitigating heat-related risks, particularly watching out for vulnerable individuals.

If you dig a little deeper, you see that:

The Health Department plays a critical role by training healthcare professionals to handle heat-related illnesses and ensuring hospitals have adequate medical supplies. They also provide public health advisories tailored to vulnerable groups.

The Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) manages cooling centers that offer respite from the heat, especially crucial for those without access to adequate shelter or cooling at home. They also ensure water availability throughout the city. Recognizing the heightened risk at exposed locations, the MCD provides shade in public areas and construction sites.

Recognizing the vulnerability of workers, particularly those in outdoor or physically demanding jobs, the Labour and Employment Department focuses on workplace safety. They promote employer adoption of safety measures and enforce regulations to prevent heat stress.

Can the flow of information between these departments be made programmatic? Can employers, schools and other institutional actors have access to the same dashboard as these departments?

It's important to note that this information is drawn from a document outlining agency responsibilities and doesn't necessarily provide a complete picture of all the vulnerable populations considered by the Delhi Heat Action Plan. Nevertheless, how is this going to be done programmatically? One answer might be: those are implementation details left to the individual departments - this plan is a high level resource.

We believe that’s a way of thinking best left by the wayside.

If you recall, in the previous Messenger, we said that planning documents should be adaptive; that one day, the flow of control might be from the IMD to the health department to the MCD and on another day it might from the IMD to the MCD to the Labour Department. Even this might be understating the complexities needed: on the very same day (say, when there’s a heat emergency), you want the MCD to be able to coordinate with the labour department so that cooling stations are made available to construction workers across the city and shades are available to the general public. As a member of that public, I should know where the nearest shaded spot is, or where I can get cold water. These problems can’t be solved with fixed architectures.

Moral of the story: A city-wide heat action plan (not just for Delhi) needs much more consideration to its architecture, i.e., how information flows from agency to agency, how non-governmental stakeholders (employers, CSOs etc) are incorporated into the execution of the plan etc. In next week’s Messenger, we will continue our discussion of heat action plan design, informed by publicly available data from Delhi.