Solving in Public I: Heat Action Plans

One mark of skill is the ability to do the right thing at the right time in the right way. Or what's often known as 'skillful means' in a religious context.

“Skillful means” is a concept rooted primarily in Mahayana Buddhism, where it is known as upāya (Sanskrit for “expedient means” or “skillful means”). It refers to the use of methods, techniques, or strategies that are tailored to a particular individual’s or group’s capacity, in order to help them progress toward enlightenment or wisdom.

If you set enlightenment aside, what role might skillful means play in addressing the challenges of collective existence? In particular, what might skillful citizenship mean? How can we be skillful in the way we approach public problems and what tools and principles might help us be so? We see public problem solving as both

the training for and

the outcome of skillful citizenship.

Citizens should be able to organize themselves to solve problems at every scale: from a hyper local need to a national emergency. Skillful citizen action isn’t a matter of getting people on to the streets - it has to be grounded in knowledge. On occasion, that knowledge will be grounded in data sources and models that require technical know-how. That’s where citizen centric design and UX appropriate to citizen action become important aspects of public problem solving. Climate change makes the need for citizen self-organization even more poignant - there will be too many challenges in too many circumstances for any single agency to address them all.

Climate citizenship needs skillful means.

In this series of posts, we bring our take on public problem solving to a specific domain: heat.

Making a Case

Let’s get this series of posts started with some thoughts on

How to gather knowledge pertaining to wicked problems,

How to document that knowledge, and

How to take actions based on that knowledge.

It's been a truism at least since Aristotle that different domains of knowledge need different levels of precision. These standards have typically emerged organically as disciplines mature, both because of internal developments and from reflections by philosophers systematizing the disciplinary standards. Of late, there's a newly surfaced need for knowledge to emerge by design, especially when it comes to complex, "wicked" problems that stretch our cognitive capacities.

Let's start with the gold standard in this domain (and in any other), which is to start with a research proposal, get funding, conduct the research, write-up the findings and go through a peer-reviewed process of publication, turn those publications into policy recommendations or advocacy positions and then see those positions affecting the world. Even if we perform these six odd steps at an extremely aggressive pace, we are still looking at a minimum of two-four years to go from idea to action, i.e., three opportunities for interventions over a decade.

That feels excruciatingly slow when experts think we have less than a decade to make drastic changes in our economies to address climate change.

Meanwhile, it's not clear we need the level of confidence in hypotheses prized by academic scholarship. Let's say there was a 1% chance the earth would be hit by a life ending asteroid in the next year: should we be spending that year doing whatever it takes to avoid that 1% scenario or redoing the calculations and arrive at a slighly more accurate number (let's say that was .5%). Does our moral calculus change when the numbers change? Probably yes, if the number went up from 1% to 10%, but maybe not so much if it went down from 1% to .5%. We need knowledge that's suited to the problem at hand, including the inherent uncertainty of the problems we are addressing.

Then there are the obvious challenges with any long chain: the incentives of the decision maker who hears the policy recommendations differ from the incentives for the researcher who writes the initial grant. Why do we think knowledge produced by the latter is useful for actions taken by the latter?

Can we do better and how?

Our answer is yes, but only if we design for knowledge. We want wicked knowledge to be:

1. Contextual - what a scientist needs from a heat index is different from what a daily wage earner needs and those differing needs should be reflected in the knowledge at hand (in both their hands, so to speak).

2. Actionable - we should be able to act upon the knowledge right away and not wait for two years. We want our knowledge production to aid ‘public problem solving,’ i.e., responses to social challenges that are framed around the public interest - ideally, for the public and by the public.

3. Adaptive - knowledge should adapt gracefully to new data and sources of information, to new agents and their epistemic needs etc.

4. Robust - The knowledge should not degrade as it hops from one agent to the next; say, from researcher to policy advocate to decision maker.

It may not be possible to satisfy all of these constraints at once - the knowledge designer may have to make trade-offs between them, but better to do so while knowing what's being traded off rather than making blind guesses. One final caveat - this exploration of knowledge design assumes that the agents are acting in good faith, that while they might be in conflict with one another, they are genuinely interested in solving the problem to their satisfaction. It's one thing to say that the fear of asteroid collision is overblown and another thing to deny it altogether because your business depends on the same pot of money that will be repurposed for asteroid prevention.

For all these reasons and more, we think the best way to argue for a data-driven approach to wicked problems is by making a case. Our cases are inspired by the legal profession with a twist: they will have more data in them than your regular legal brief does, and more design considerations than a typical legal brief.

Case = legal brief + design brief + data + models

By the way, a case doesn’t have to read like it was written by a lawyer; we want to make a case understandable to the ‘Aam Aadmi,’ the proverbial man on the street who needs robust guidance on how to live their life amidst the varied challenges and opportunities they face.

Now that the preliminaries are out of the way, we want to get into the business of picking a wicked problem and making a case for responding to it. Somewhat meta, but we want to make a case for making cases by showing how we arrive at the case we are making. It’s not enough to say: here’s the case for X or Y; public problem solving demands that the logic behind case making is as transparent as possible. Give someone a case and they will solve a problem that day, but if you teach them how to make cases, they will solve problems for a lifetime.

Heat Waves in Delhi

There are many wicked problems in the world; in fact, there are many wicked problems for which a case can be made in the way we want to make them. So it was a bit difficult for us to make a choice, but we ended up making a case for exploring heat waves in Delhi.

Let’s zoom out a bit and look at heat waves across North India. Heat waves in North India have become increasingly severe and frequent over the past few years, largely due to climate change. To give a brief overview of the past three years, in 2022, North India experienced an extreme heatwave from March to June, with temperatures reaching up to 49.2°C. This heatwave resulted in at least 90 reported deaths (though we think the number is far higher) and was noted as the hottest March in India since records began 122 years ago. The number of heatwave days in May increased by 125%, indicating a significant rise in the frequency of such events.

The heatwave in 2023 spanned from April to June, with temperatures peaking at 46.2°C. This period was marked by extreme humid heat, which exacerbated the health risks associated with high temperatures. The consistent high temperatures across a vast region and over many days highlighted the persistent nature of heatwaves in recent years. The summer of 2024 has been the hottest ever recorded in North India, with temperatures exceeding 50°C in many parts of the country. A sensor in Mungeshpur in New Delhi recorded the mind-blowing temperature of 52.9°C, but that number has been disputed, with GoI asserting it was 3° too high. Still, 49.9° isn’t exactly pleasant weather is it? The extreme heat forced schools to close early for the summer, and nighttime temperatures remained as high as 36°C in some locations.

We can cite more statistics, such as the loss of livelihoods, stunted learning outcomes because of school closures, loss of agricultural productivity or the harm done to non-human species such as birds and bats, but there’s no real need to do so:

The visceral discomfort experienced by hundreds of millions of people experiencing scorching heat for months on end deserves urgent redressal, and this is a recurring situation where data can help make a nuanced case for public health measures.

North India is a bit much for us to analyze, at least in a manner that leads to public problem solving. We want to focus on a geography where a data driven approach can feed decision making by various parties, from truck drivers to building contractors and the state, and each stakeholder’s decision helps make the place better for others who inhabit it. Therefore, we chose Delhi as the unit of analysis. It’s small enough, has workers and employers of every kind, it has experienced overwhelming heat and will continue to do so, and has a state government that has the capacity and perhaps the desire to address the problem at scale.

As it turns out, Delhi already has a heat action plan, but is it the kind of plan that’s designed for actionable knowledge in the way we outlined earlier in this essay?

Has the Delhi Disaster Management Authority’s Heat Action Plan been designed for knowledge?

A quick analysis of the DDMA Heat Action Plan 2024-25 is sufficient to see why it has not.

A contextual plan must use reliable data and properly. While several of the statistics and charts pertaining to rising temperatures and demographics in the DDMA plan have been cited as being sourced legitimately, the sources of some have not been mentioned. Similarly, artifacts in charts - such as trend lines and categories - have not been sufficiently described. We stress that these are not pedantic issues, but rather important issues pertinent to the government’s accountability. Furthermore, at the heart of the contextuality issue is the question of relevance: whereas we appreciate the DDMA’s effort to identify vulnerable segments of the public, such as the economically marginalized, women, children, the elderly, and workers particularly exposed to the sun, such as construction workers, we barely find actions specifically aimed at protecting them. The lack of representation of the truly different needs of diverse members of civil society is conspicuous.

In terms of actionability, we have three major concerns. One: the DDMA heat action plan notes the dire economic impact of extreme heat and yet presents no plan of action to insure the loss of livelihoods among vulnerable segments. Without such insurance, the DDMA's planned actions may at best be seen as superficial attempts to address the impending health crisis – merely applying a bandage rather than stopping the bleeding – as vulnerable members of society are forced to choose between working in deadly heat or protecting their lives. Two: whereas some effort has gone into assigning roles and responsibilities (though, largely, to state agencies alone), various actions expected of different parties are identical, creating further confusion and inefficiencies. Three: planned actions are not specific – for instance, would the action to repair/provide cooling in public transport be “complete” if fans were installed in a handful of buses? Thoughtful, measurable objectives need to be devised for any extreme heat action plan to have tangible impact.

For a problem as complex as responding to heat waves in a state with a diverse socio-economic civil society, the annual time-frame of the DDMA’s heat action plan is too long a window, divorcing it from real-time complexity on the ground. For instance, the plan identifies 10 vulnerability hotspots, presumably to better support residents in those spots, but because there are several other “thermal hotspots” that the plan itself identifies, one of the latter locations may well end up requiring greater support in reality. An adaptable plan ought to clarify exactly how to adapt the plan, on what grounds the plan should or should not be adapted, and who would be accountable for such adaptations. Moreover, while some planned actions cover the need to collect data pertaining to temperatures, hospitalisations and other emergencies, there is no plan to make these data public, nor is there mention of any feedback loop for real-time adaptability.

Finally, the DDMA's heat action plan exhibits attributes that diminish its robustness. First, although a digital copy of the plan is available to the public, where we do believe it belongs, it is entirely in English and devoid of graphical cues that would aid the general public in understanding it. This language barrier and absence of visual aids impede effective communication to non-English speakers and individuals with varying literacy levels, leading to degradation of knowledge as it is transmitted from policymakers to the public. Second, as mentioned earlier, several actions assigned to responsible parties lack detailed specifications. What makes this a robustness issue is that this lack of precise delegation allows for willful or unintended degradation of specific expectations as orders are issued down the administrative hierarchy, creating the risk that implementers misunderstand or neglect their duties. Collectively, these issues present challenges for transparency in the public domain as well as risks to the plan’s integrity.

We don’t have a special complaint against Delhi’s heat action plan - it’s a government report like many others. However, we don’t think it makes the case for action in the way we believe aids public problem solving. In next week’s essay, we will start with a discussion of design choices that will make heat action more citizen friendly. In our opinion, of course - we don’t have pretensions as to this being the best case that can be made, but at least it starts to make a case.

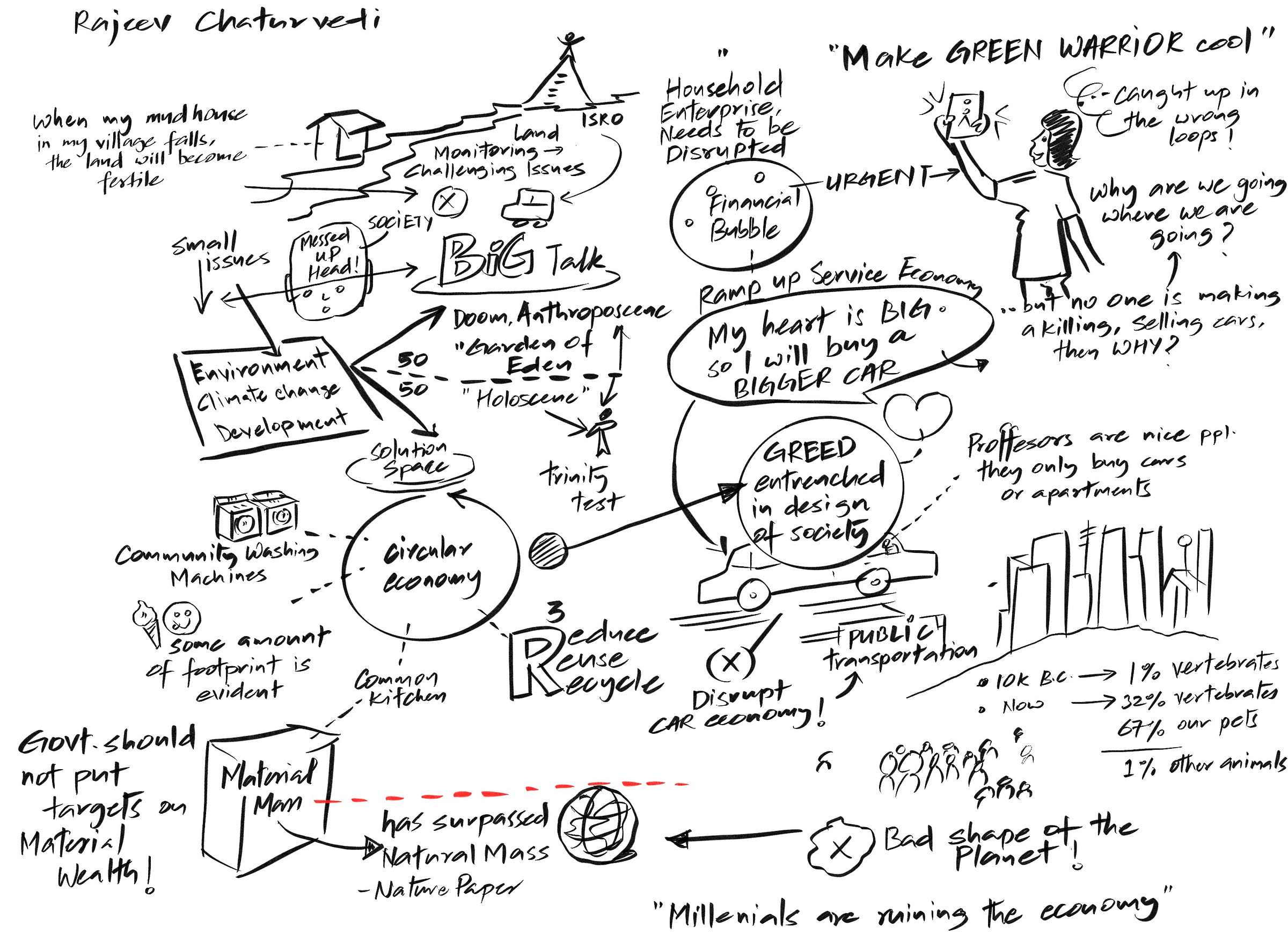

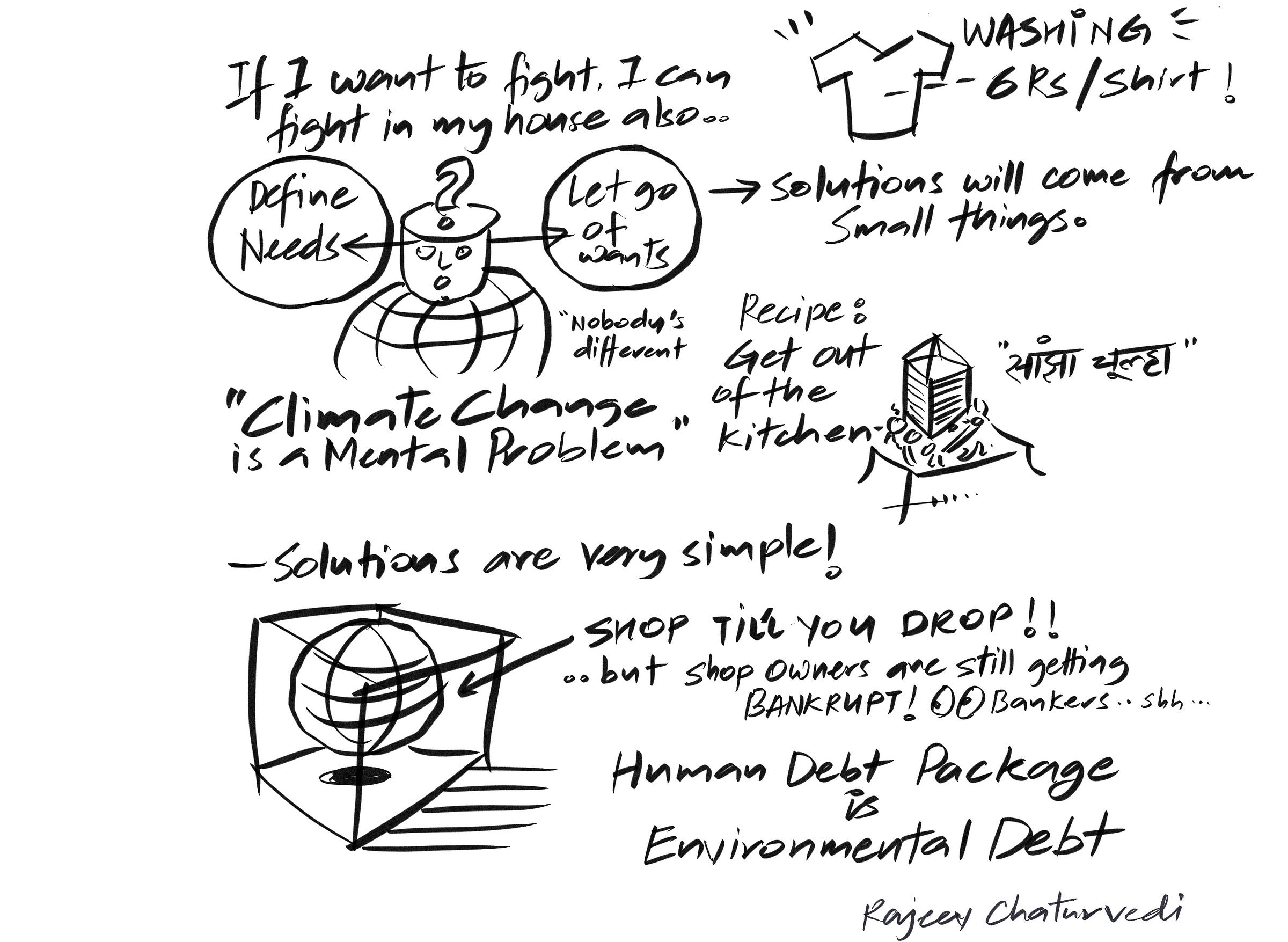

Climate Recipes

“Climate change is a mental problem” - Rajeev Kumar Chaturvedi (Assistant Professor, BITS Pilani, Goa Edition)

The shifts in the climate worry us and induce stress, but the moment we think about solutions, it is empowering. We are in a time where the materials humans have produced have surpassed the mass of trees and animals on the planet. To survive this shift, we have to adapt to the circular economy of Reduce - Reuse - Recycle. Some emissions are inevitable, and we can’t do much about them. But we can control the additional load on the planet by letting go of personalized vehicles and appliances and working towards shared solutions. We humans should meet our needs and not let greed take over.