Living with Others, Part 4: Salt in the Balance

Once upon a time, there was a clever monkey who lived in a fruit-laden tree by a river. One day, a crocodile swam up to the tree and, seeing the delicious fruits, asked the monkey for some. The kind-hearted monkey agreed and tossed a few fruits to the crocodile. This became a daily routine, and the two eventually became friends.

The crocodile, impressed by the sweet fruits, decided to take some home to his wife. However, after tasting them, the crocodile’s wife became greedy. She convinced her husband that if the fruits were so sweet, the monkey’s heart, who ate them daily, must be even sweeter. She then demanded that her husband bring the monkey to her so she could eat his heart.

The crocodile, torn between his loyalty to his friend and his wife’s demand, reluctantly agreed. He invited the monkey to ride on his back, promising to take him to another tree with even more delicious fruits on the other side of the river. The monkey, trusting his friend, agreed and climbed onto the crocodile’s back.

As they swam across the river, the crocodile revealed his true intentions. The clever monkey, realizing the danger, remained calm and told the crocodile that he would gladly give up his heart, but unfortunately, he had left it on the tree. He suggested they return to the tree to retrieve it. The crocodile, eager to fulfill his wife’s wish, agreed and swam back to the tree.

As soon as they reached the tree, the monkey quickly climbed up to safety and scolded the crocodile for betraying his trust. The crocodile, ashamed, realized his mistake and apologized. The monkey, though forgiving, was cautious and never trusted the crocodile again.

But crocodiles have to eat too, don’t they? How else will they survive?

Salt

As you step foot into the Bhitarkanika landscape, you are immediately greeted by that familiar coastal sensation of heavy air on skin, a breezy and sweaty reminder of where you are in relation to the ocean. Speaking to people in Bhitarkanika, you realise that this sensation, this orientation to the land and sea, is not just skin deep. This week’s messenger is about reorienting ourselves in this way…

In a conversation with a co-passenger in the bus to Rajnagar, they said “humara namak wala area hai”. After a pause he explained further, “jaise humara paseena hota hai na” (Ours is a salt area. Just like our sweat). He works as a plumber and was returning home to his village near Rajnagar. But this personal description of the landscape, for the uninitiated inlander, was telling. Everyone is aware of the importance of water in the scheme of life, but it’s rare that people put salt on a pedestal. As we have been immersing ourselves in the coastal Odisha landscape over the past few months through our various interventions, the relationship between saltiness and life has been central - albeit as part of the backdrop uptil this point.

The number of ways that plant and animal (including human) life in the region have adapted to salinity makes one appreciate the uniqueness of mangrove ecosystems. Scientists have categorised species of mangrove according to how they deal with salt (poop out/keep out). Some species have salt glands in their leaves that excrete the salt absorbed from the water back into the environment. The aerial roots of some mangrove species have also developed as a response to the high salinity and reduced oxygen content in the water and soil. These characteristic aerial roots, or pneumatophores, have tiny pores called lenticels, which then shut tight during tidal inundation to keep the saltwater out. They are basically snorkelling.

Even the seemingly unassailable saltwater crocodile, despite the name, lives in brackish water habitats and can’t handle the open seas where the water salinity is much higher. They have salt glands on their tongues to eliminate excess salt in their bodies. So reports of crocodiles venturing further and further away from their habitual dwellings and closer to human settlements, especially in the drier summer months, are partly because of the continual ingress of saline sea water further inland. Such is the centrality of saltiness to this world that the word one of the words for mangrove forest in Odia is luna jungle or salt jungle. The invocation of sweat adds a different dimension to the story - of toil, of the challenges of living in an environment that is at once resilient and fragile. It is this finely poised balance that is at stake now, with findings about coastal erosion, sea-level rise and mangrove degradation threatening to tip the scales. We spoke last week with people in Bagapatia, a village of climate refugees who were forced to leave their homes in Satabhaya because the sea ate it up. A man told us of how he stood on the Satabhaya shore in the aftermath of cyclone Fani in 2019, to see school desks floating 2 km off in the distance, where the school used to be.

On Achieving Balance

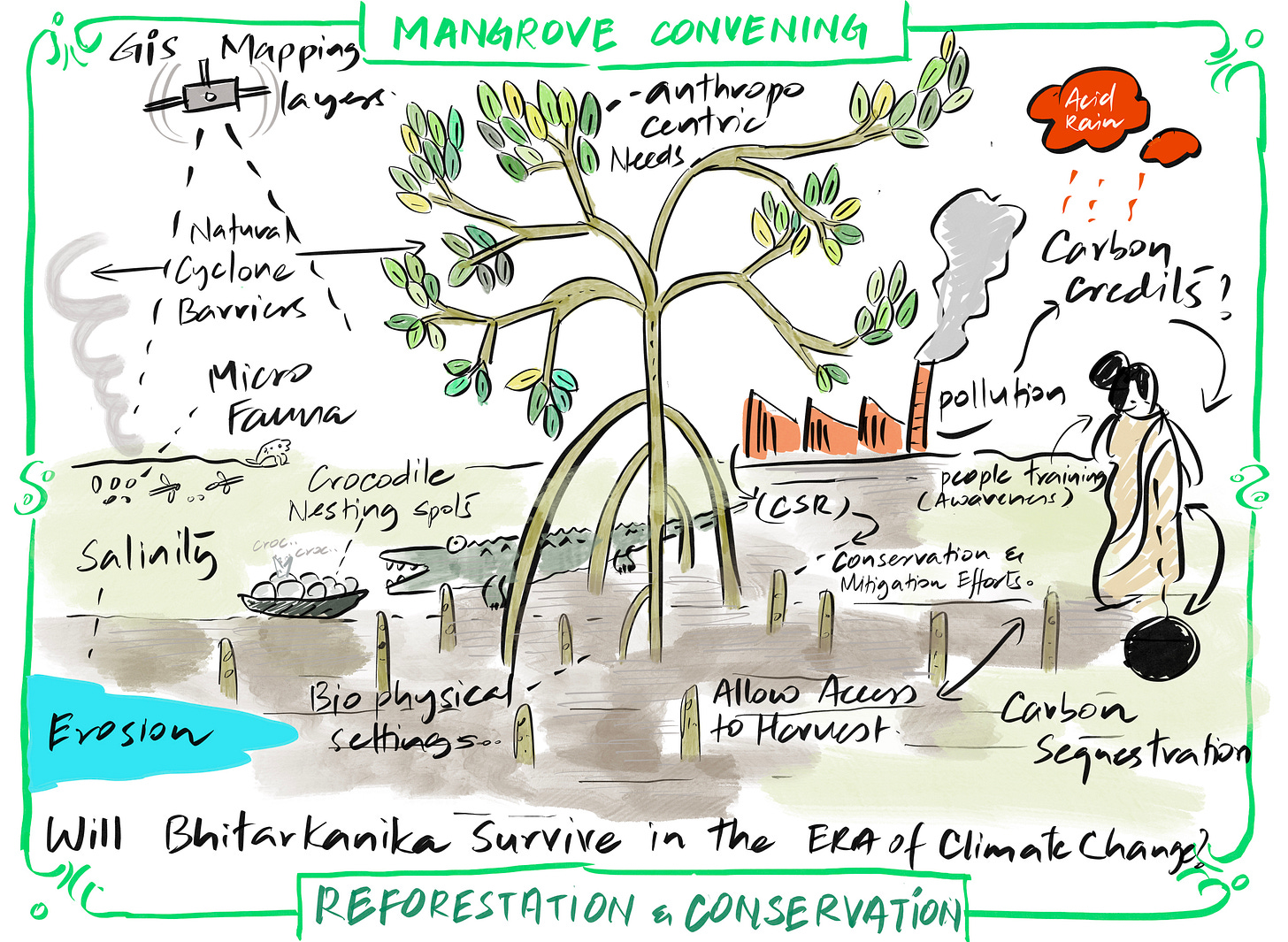

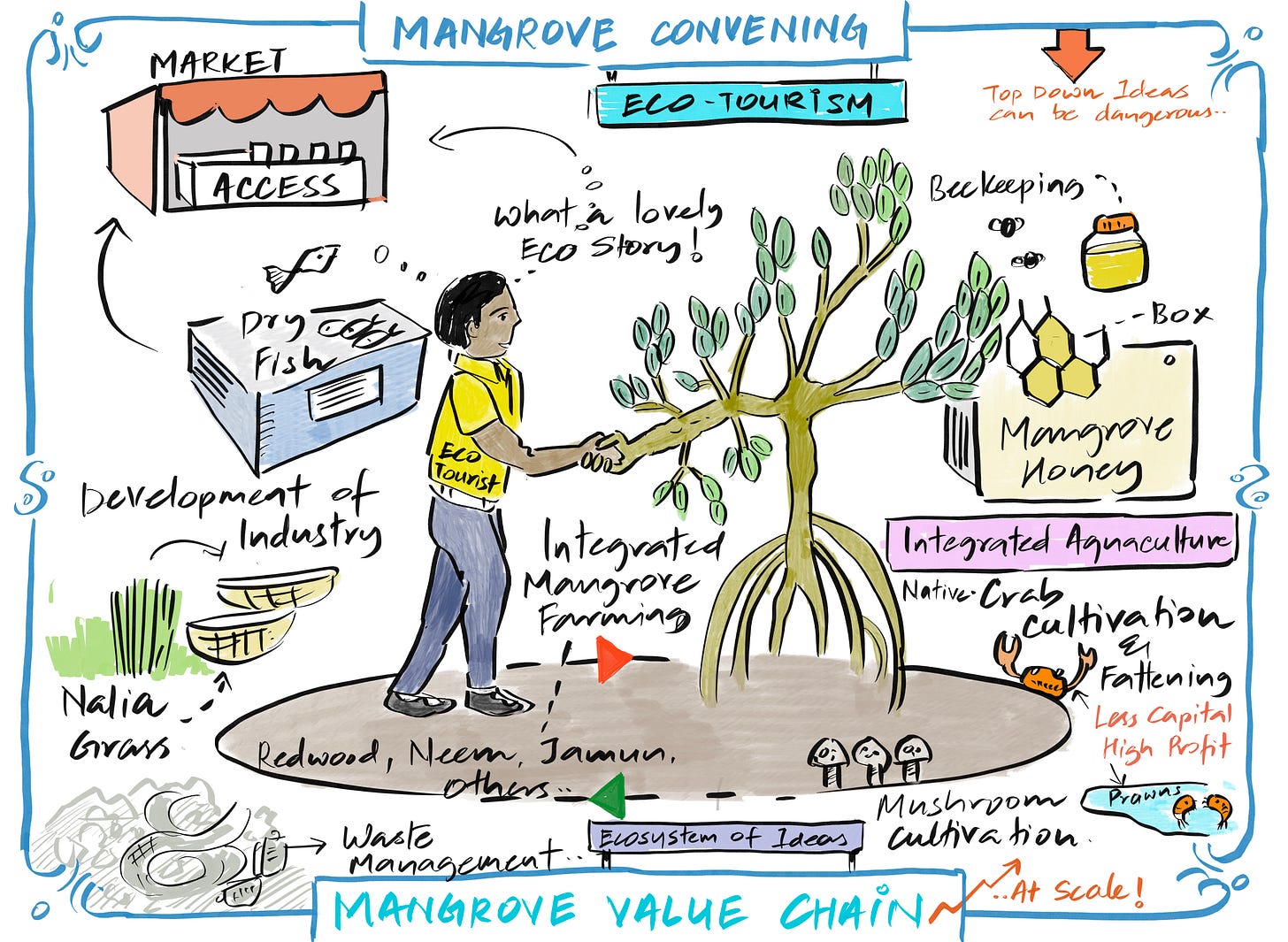

Over the past year, we have been working extensively in this coastal landscape, trying to enact our theory of change through various interventions in mangrove conservation and livelihoods- a thorough appreciation of which will require its own dedicated Messenger series. But for now, one part of this is to understand the contours of human-wildlife co-existence in Bhitarkanika, with special reference to the human-mangrove-crocodile interface. As part of this action research effort we are working to bring into conversation voices from the local community, from the wider ecological and herpetological research community, and from the forest department to develop models of coexistence that promote mutual flourishing. A first step toward this was the Citizen’s Jury that we, together with Nature’s Club, organised in July where representatives of each of these stakeholder groups deliberated for a day on the themes of livelihoods, human-wildlife co-existence and mangrove conservation. Again, this is a very delicately balanced issue, but for the moment we leave you with some anecdotal provocations based on our ongoing ethnographic research.

At the heart of the matter is that the mangrove ecosystem of Bhitarkanika is under stress, due to climate related and population pressures. As per the census, the population figures have consistently risen each decade. This is paired with the success of the government’s crocodile conservation project that commenced in 1975, and a rising population of crocodiles through a rear-and-release programme in the national park. The rearing programme is reported to have been stopped this year as the crocodile population has “reached its saturation point”. Despite this jostling for space, when asked if he was fearful of crocodiles, a man simply replied “humara pet hai, unka bhi pet hai” (they have a stomach to feed just like us).

An important thread that is emerging through our interactions is an apparent disconnect between the people and their land. This discontentment was expressed to us in a few different ways. In one, the same old man referenced above explained how the forest and human communities depended on each other. When he was young, they used to go into the forest for honey and fruits, for wood to build their houses and for other resources. But the restrictions around entry and activity in the national park is a source of a kind of sadness. Even so, the phrase “hental van aamar suraksha kavach” (the mangrove forest is our protective shield) rung out loud and clear in a Climate Panchayat we organised in Rajnagar last week.

This delicate balancing act is something that will need to be worked out in practice, so we shall see how we get on.

Climate Recipes

Research Edition: Coastal landscapes of Odisha

“However dangerous the animal in the forest, I don’t see them as a threat” - Nilamani Behera, Crocodile caretaker and hatchery expert, Bhitarkanika National Park

I began my career as a forest guard dedicated to the conservation of majestic estuarine crocodiles. Reflecting on my first day of work, which set the course for my future, I remember being tasked with collecting crocodile eggs from different nests to establish the initial stages of the hatchery. This directive came from Dr. Bustard and Dr. Sudhakar Kar, the crocodile experts at the time. Dr. Kar instructed me to venture into the mangroves to collect the eggs.

Over the years, I have gained extensive experience, having rescued nearly forty crocodiles from villages, ranging from 6 to 15 feet in length. I consider the crocodiles I rescue to be my children. You may doubt my words, but I can communicate with them. I scold them when they venture into nearby villages and create trouble. Just as children possess less maturity and act on instinct, these crocodiles can be dangerous, yet my love and respect for them remain unwavering.

No matter how dangerous these animals are, I do not see them as a threat. For me, they are not merely creatures of instinct but beings deserving of care and respect.