Living with Others, Part 3: The Multispecies Times

As alluded to in last week’s messenger, our work in various settings – urban, rural, coastal, mountainous – and with varied interlocutors in these places, has always seemed to hint at the importance of a framework of flourishing that is explicitly multispecies in its approach. This is meant not in the narrow sense that we take as our focal object a particular species, but rather that we actively bring it to the fore the relationships not only between and among humans but also across species bounds.

A first step toward articulating this framework over the past year has come through our work with street dogs in India. More specifically, we embarked on a project to reshape prevailing narratives around human-dog coexistence against the backdrop of increasing polarisation and intolerance regarding the presence of dogs in our cities. This led to a fascinating few months exploring the wonders of urban biodiversity – learning about the importance of species such as dogs, black kites, and macaques to urban ecosystems; about ecological niches, metabolic flows and the fascinating behavioural adaptations of urban-adapted species; about the importance of assessing dog population densities in order to determine the risk of rabies transmission; and from media and conservation practitioners on how best to convey the importance of multispecies coexistence to a general audience – to name but a few important stakeholders we have been speaking to.

The thinking behind undertaking this work with street dogs was to seriously engage with the idea of co-existence as not only something to be done “out there” in some beautiful, far-flung corners of the country but as an ongoing practice that we are already engaged in our daily lives. This helps to reorient ourselves, to step away from the supposed division between “wilderness” (the prototypical site of coexistence) and “civilization”. For many of us city residents, interactions with dogs are the most common types of multispecies encounter that we immediately recognise as such.

What if we begin to see their stubborn presence on street corners as expressions of their legitimate claim to city space that exists alongside our own? Further still, what if we come to accept the neighbourly gutar-goo of the pigeons that have made their nest above our windows? Can we appreciate the complex subterranean pathways of the rats who call our cities home and have seen parts of it that we never have? And what of all the innumerable species recycling organic waste and dead matter, and keeping each other in check - they all have a part to play. The rapid decline in urban sparrow and vulture populations should give us pause and teach us to value the presence of those that choose to remain. Even mosquitoes - maybe they have the legitimate right to suck our blood and buzz in our ears? Or maybe not, we’re still trying to figure that one out.

But back to our more loveable urban cohabitants for now. Unlike pet dogs, free-ranging dogs living their lives to their own rhythms alongside human communities, present something of a challenge to our neat conceptual boundaries – neither wild nor tame; familiar but unknowable; pets but also pests... Occupying these margins, they have found ways to live in India's disturbance-based ecologies, and can offer ways to rethink the urban as a site as solely the domain of humans. In a different register, street dogs also offer ways to think of the urban poor, whose ways of being in the city are condemned to the margins of the urban imagination through discourses around safety and hygiene, conferring them a somehow less-than-human status.

“The nature of complaints we receive from low vs high income neighbourhoods is very different” said a community engagement practitioner who works on resolving disagreements around human-dog conflict. “People who are particularly from the wealthier parts of society, I think their problem is rarely zoonosis or violence, their problem is inconvenience, but they shoot from the shoulders of violence.”

A lot of media and popular discourse further confound the issue, through the use of tropes such as “man’s best friend” or the looming “dog menace”. These essentialising and misleading tropes divide people into opposing camps and prevent meaningful dialogue from taking place. Little known to them, street dogs carry with them so many of our hopes and fears.

And while these aspects dominate our conversations, it obscures focus from efforts to address the thorny issues around the drivers of conflict and what can be done about it. Nishant, an ecologist we spoke to used an interesting analogy to convey a similar thought in relation to how we tend to talk about human-dog conflict,

“What we do, unfortunately, is do firefighting, not fire management. In protected areas, very thorough fire management is done. So you have to create a fire line and then you have to gently broom it, remove all the potential litter, which might become fodder for fire. So good fire management prevents fires. Otherwise there is no possibility of controlling fire if it breaks out. And if it happens that we have not been able to manage it well in a given area, then it is largely due to poor management of litter on the fire line. I precisely use firefighting because everybody knows that fires would occur. In the same sense, one should realize that conflicts would occur. When there is a clear indication of a conflict with the non-human cohabitants of the city, why can't we be prepared? Why does it have to be reactive and a knee jerk reaction every time?”

One outcome through this project then, has been to turn the lens back on ourselves. What can we do to promote more nuanced public conversations around human-dog coexistence and conflict, and more scientifically informed debates around the kinds of interventions that are feasible and can promote mutual flourishing?

A key partner we identified in this effort has been the news media. We published this article in The Hindu about the importance of getting in the weeds to try to tell more nuanced and complex accounts of our multispecies shared spaces. In collaboration with the Dog Lab at IISER Kolkata, we also organised a convening with journalists at the Press Club in Kolkata to explain the importance of sensitive, and scientifically informed coverage of human-dog conflict. We spoke about the problems of over interference in the lives of free-ranging dogs and about the relative success of the government’s long-term rabies prevention efforts. This will be part of a series of media convenings with the next scheduled to take place in Chennai next month.

We have also been speaking to different profiles of individuals whose expertise has some bearing on human-dog relations including ecologists, canine behaviourists, public health experts, urban planners, dogs, humans, waste management experts and legal practitioners in an attempt to compile relevant insights from varied disciplinary and experiential standpoints. Earlier this year we held a closed door stakeholder convening with a subset of these experts. The convening was designed to enable a dialogue between people who might not usually find an occasion to, and in so doing, break down disciplinary siloes and conceptual impasses. It was a mixed success. Serenely above the finer protocols of human stakeholder convenings, the dogs remained absent from these gatherings.

Maybe if we find ourselves at a dead end, the only direction of travel remaining is upwards - to take a flight of fancy, a leap of imagination. A wise old philoflaneur once said, “You’ve probably heard a thousand stories that begin with ‘once upon a time.’ Can you name one story that begins with ‘once upon a place’?” We might then ask ourselves, what could proximate versions of our cities look like in the not too distant future, where animals in the built environment are not seen as an afterthought but are recognised and valued for their central contributions to urban life - positive as well as negative. What if the city plan had a wider conception of urban space and contained a chapter on the affective dimensions of human-animal co-existence, with room for the spontaneous expressions of love, compassion, anger, fear that we have all experienced in our multispecies encounters…

Climate Recipes

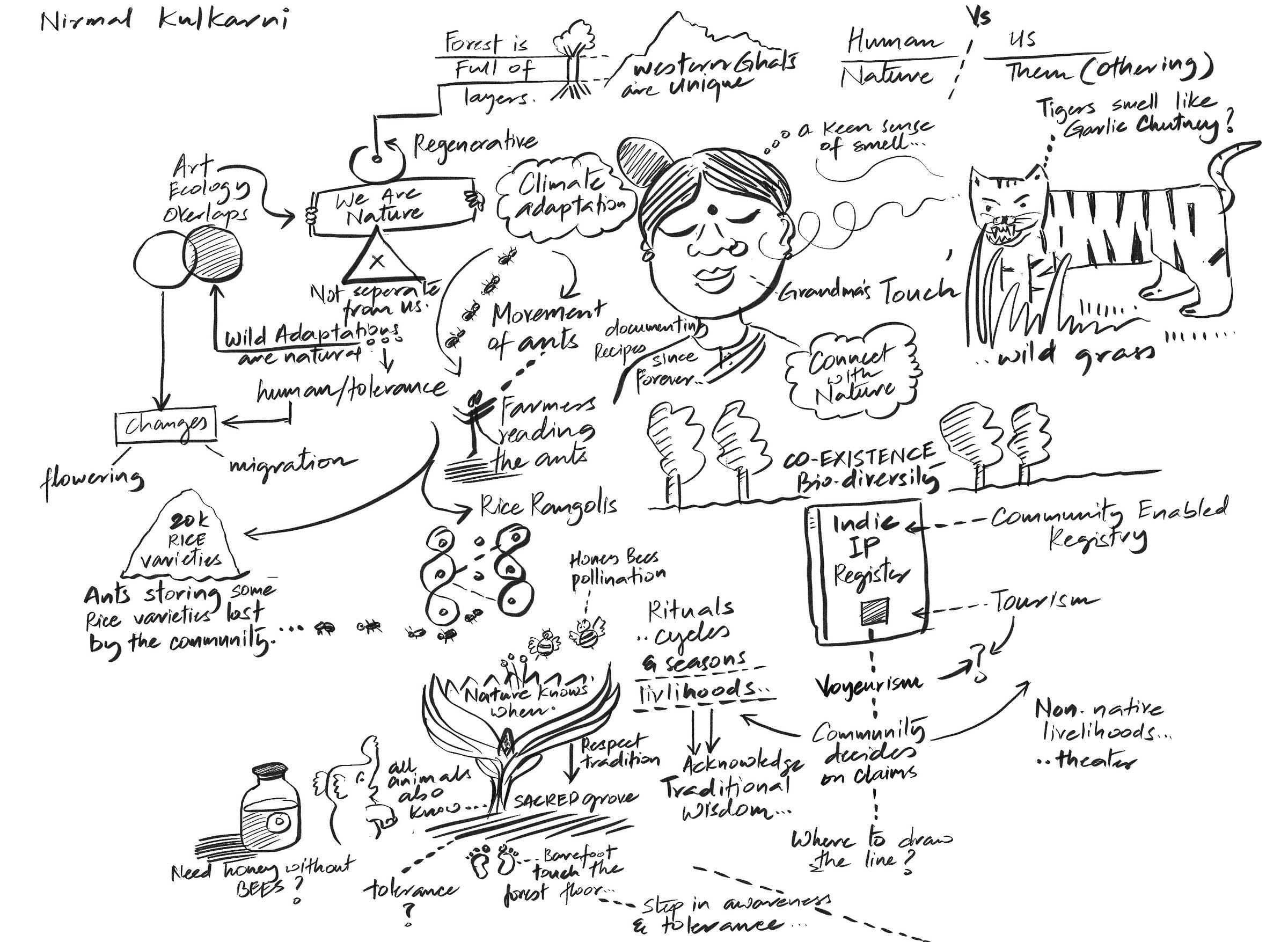

“Tiger smells like garlic chutney” - Nirmal Kulkarni, Goa Edition

If you smell garlic chutney in a forest, brace yourself since a tiger might be around. Engaging with the forest means sensory activation, where smell and touch become your pathfinders. When you enter centuries old sacred groves with bare feet, you respect ancestral beliefs and traditions. By this gesture, the sacred grove is also accepting you and letting you overcome the fear of the wild step by step. When we touch the ground, we sense the space of tolerance and cohabitation. The forest and its plant and animal habitat are our mentors of climate resilience and adaptation. It is time we establish a connection and learn from them.